Introduction – In this two-part essay I will endeavour to place the life of the Tasmanian Aboriginal resistance fighter William Lyttleton Quamby into the context of his place and time.

Part 1 describes what is known about Quamby’s life; and Part 2 using contemporary nineteenth-century maps of land grants to British settlers will show how the traditional Aboriginal fire-farmed plains on either side of Quamby’s Brook at Westbury were handed over to the settlers by the colonial government over a period of about 10 years from 1824. This was the same decade in which Aboriginal retaliations for loss of their land escalated into the Black Wars.

The current and controversial debate about the location of a new prison in northern Tasmania near the village of Westbury shows little or no understanding or consideration of Tasmanian history. It is salutary to reflect upon some of the issues from the past which resonate directly with the present. For it is in the centre of this ancient fire-farmed Aboriginal landscape of Blake’s Plains and Emu Plain divided by Quamby’s Brook, now overlain by an Anglo-Irish farming landscape that stretches from Hagley to Deloraine, that a prison is proposed to be built by the Tasmanian government.

Westbury adjoins these two plains to the south and survives virtually intact as planned in 1826 with its magnificent bluestone Roman Catholic church, a village green and a grid pattern of streets laid out by Lieutenant Thomas Shadforth of the 57th Regiment. It has direct connections with the history of Irish settlers, some of whom took up five-acre land grants in the town in the early-nineteenth century after being discharged from the British Army or as freed convicts, or like Richard Dry and William Bryan received large grants. Scottish settlers had already taken up farming land to the south in the Hamilton and Bothwell districts and on to Lake Echo, leaving the Irish and others to seek land then being opened up in the north-west of the island along the Western River (Meander), Mersey and Quamby’s Brook.

Four white settlement Tasmanian estates either adjoin, surround or are part of the ancient Aboriginal hunting grounds which the settlers renamed Blake’s Plains and Emu Plain. These two former fire-farmed landscapes are divided by Quamby’s Brook which runs from Quamby’s Bluff to the Meander River. The four estates were created by the Dry family at Belle Vue (later Quamby), the Field family at Westfield, William Bryan at Glenore and Lieutenant William Lyttleton at Hagley and they all contribute to the creation and appearance of the Westbury landscape as we know it today.

In the eighteenth century, many young Africans and Indians were taken from their places of origin, often through the slave trade, to work as household attendants for wealthy families in Britain. Their duties were not necessarily onerous; their chief function was to look decorative. Serving as the human equivalent of a fashion statement, they were considered exotic ornaments complementing the porcelain, textiles, wallpapers and lacquer which the British were importing from India and the Far East.

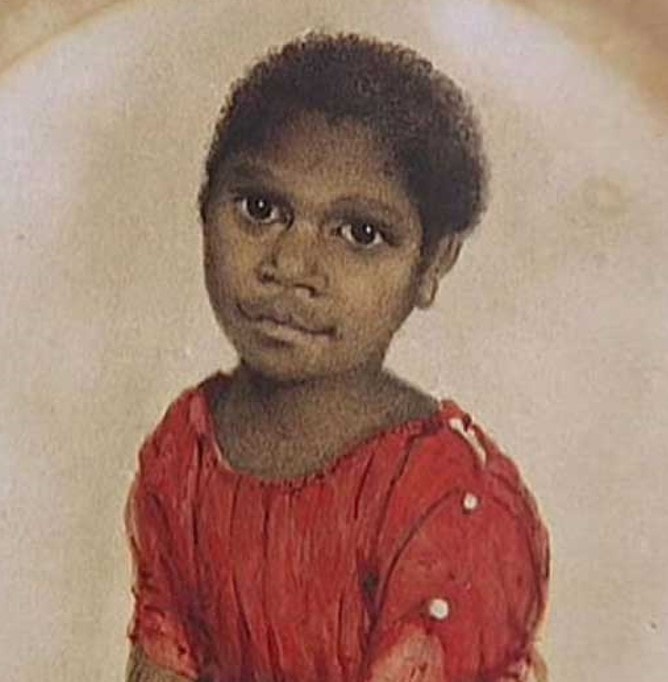

Portrait of Mathinna, painted by Thomas Bock for Lady Franklin. Detail of watercolour. Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart.

Many slaves who came to Britain were brought back by planters, government officials or military and naval officers returning from service overseas. One example was Captain Lachlan Macquarie, later Governor of New South Wales, who married his first wife Jane Jarvis while stationed in Calicut, India, where he purchased from the slave market in Cochin a five-year-old boy for 85 rupees. He named his slave George Jarvis and Jarvis travelled with him as his soldier-servant throughout India, on to Egypt, to Scotland, to Australia and back again to the Isle of Mull in the Scottish Hebrides over a period of twenty-seven years.

The tragic story of the Indigenous girl Mathinna (1835-1852) and her association with Lady (Jane) Franklin, wife of Sir John Franklin, Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (1837-43) is well known in Tasmanian history.

Mathinna was taken from her own people as a young child and exposed to the luxurious but alien environment of Government House in Hobart, Mathinna experienced both the best and the worst conditions faced by Tasmanian Aborigines in the mid nineteenth century.

Jane Franklin, wife of the governor of Van Diemen’s Land, had developed an interest in the Tasmanian Aborigines. Like almost all the British, she believed in the ‘great chain of being’, a ranking of races that predated evolutionary theory, with Europeans at the top and everyone else in descending order according to their degree of observable ‘civilisation.’

Indigenous people were seen as scientific curios and Franklin wanted to learn as much as she could about them. It was this thinking that led Europeans to take children in ‘for their own good’, creating the first generation of stolen children. Franklin was one of the earliest Europeans to try her hand at Europeanising Indigenous children. 1

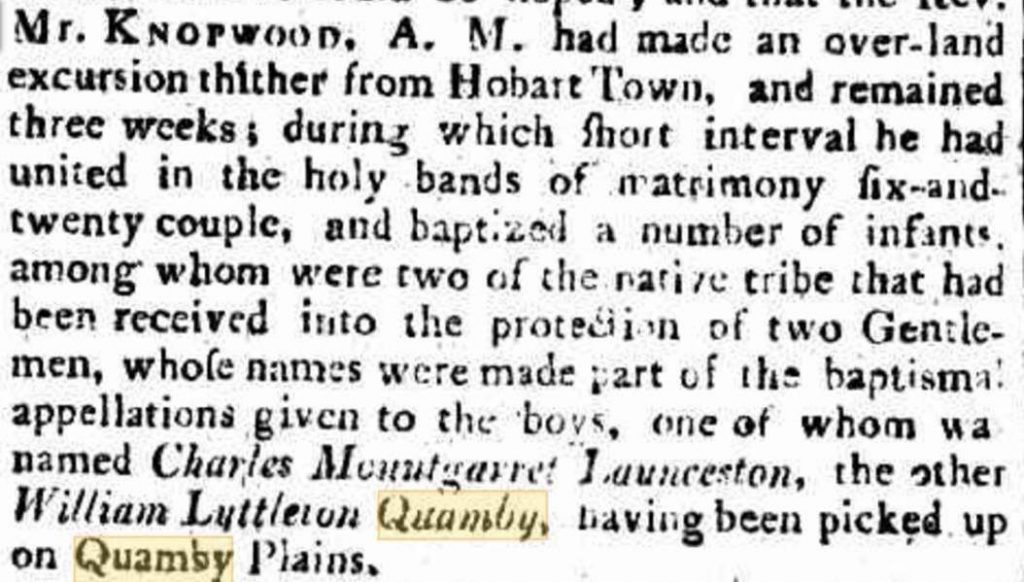

Twenty-four years before Mathinna was born, two Aboriginal children were baptised by the Reverend Robert Knopwood at St John’s Church, Launceston on 18 March 1811. One was given the names ‘William Lyttleton Quamby’. 2 The Sydney Gazette of 4 May 1811 (see extract above) reported on the ceremony, adding that that he had ‘been picked up on Quamby Plains’ hence his naming. From this it would seem that Quamby was found or ‘collected’ probably in late-1810 or early-1811 and taken to the farm of William Lyttleton at Hagley in the vicinity of Westbury near the brook which still bears his name. The ages of the two boys were not given in the Gazette report.

This first mention of the boy Quamby is significant for a number of reasons, not least because it provides the Tasmanian Aboriginal community with a reason to protect what later became known as Quamby’s Brook which still divides the two former Aboriginal fire-farmed plains where it adjoins the suggested site of a new prison in northern Tasmania.

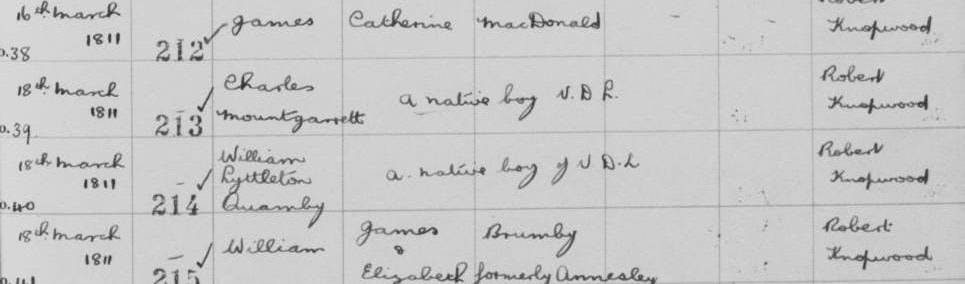

From the Baptism register of the Parish of St John’s, Launceston, 1811: baptism no. 39: ‘Charles Mountgarrett a native boy of VDL’; and no. 40 ‘William Lyttleton Quamby a native boy of VDL’, both on 18 March 1811, the 213th and 214th children baptised in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. 3

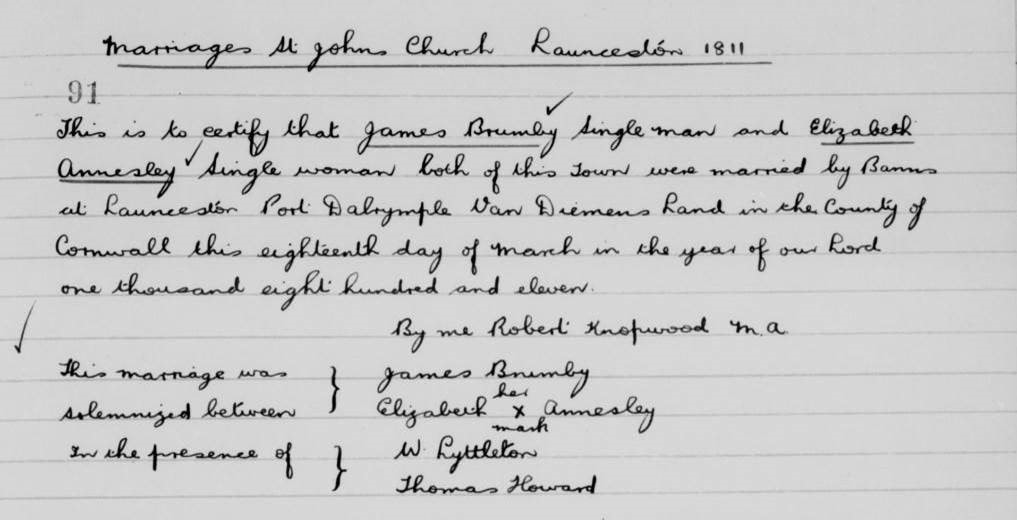

The two other children baptised on this day were William and John Brumby, children of James and Elizabeth Brumby who were also married on the same day, one of the witnesses being Lieutenant William Lyttleton. All these ceremonies were conducted by the Reverend Knopwood. It could perhaps also be surmised that Lyttleton had passed William Lyttleton Quamby into the care of James and Elizabeth Brumby whose farm was in the same district as Lyttleton’s.

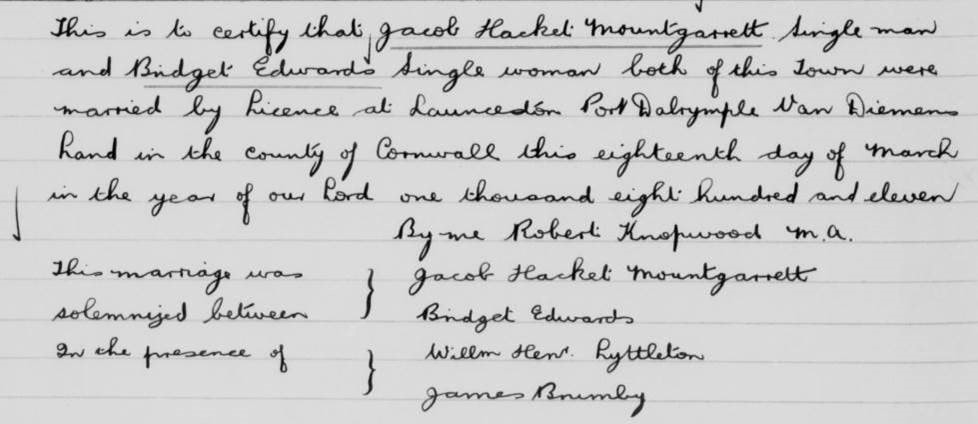

Marriage register of Parish of St John’s Launceston recording the wedding of Irish-born ships’ surgeon Jacob Mountgarrett and Bridget Edwards on the same date, 18 March 1811, as the other baptisms and marriages described here. Note that Lyttleton and Brumby were the witnesses. Mountgarrett was the guardian of the other Aboriginal boy, Charles Mountgarrett Launceston, baptised at the same time as William Lyttleton Quamby.

James Brumby was born in 1771 in Lincolnshire, England and died in 1838 at Longford, Van Diemen’s Land. He was a former soldier in the New South Wales Corps who came to Van Diemen’s Land with Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson’s detachment, landing at Port Dalrymple in November 1804. After his discharge from the British Army in December 1808 he remained as a settler and landowner in Van Diemen’s Land until his death. He married an ex-convict Elizabeth Annesley (or Ainsley or Ainslie), also from Lincolnshire, on 18 March 1811 at St John’s Church, Launceston – the same day as the baptisms – with William Lyttleton as one of the witnesses. The Australian Dictionary of Biography entry for James Brumby states that:

… James Brumby through his own efforts progressed from a private soldier to a well-to-do landowner. He was always ready to help others … and there are instances of his kindness to the Aboriginals … 4

James and Elizabeth had six children, of whom William (1804-1841) and John (1807-1825) were baptised on the same day as the two young Aborigines. The immediate circumstances of the two Aboriginal children after their baptisms are unknown but both would almost certainly have learned English and remained at least for a time with their adoptive families.

Also part of this closely connected group of settlers from the Westbury and Cressy districts were the Irish ex-convict political prisoner Richard and Ann(e) Dry who witnessed the marriage of Thomas Howard and Elizabeth Mills at Launceston on 12 March 1811. 5 Thomas Howard, the second witness at the Brumby marriage, was a free settler with a substantial business at the time selling meat to the government store in Launceston.

Knopwood’s visit in March 1811 was his first to the north of Van Diemen’s Land and over a three-week stay he christened 31 children and married 26 couples. 5 On a later visit Knopwood officiated at the confirmation of the marriage of Lieutenant William Lyttleton to Ann Hortle (or Hortell), daughter of an ex-convict, a private in the New South Wales Corps, on 21 March 1814 at Port Dalrymple. Jacob Mountgarrett had previously solemnised the marriage on 14 January 1811 in his capacity as J.P.

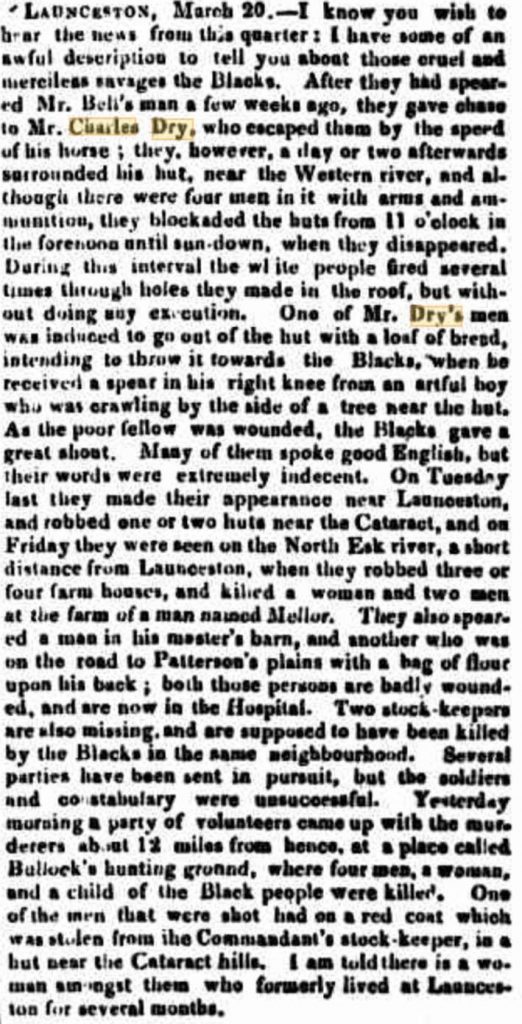

A clue about William Lyttleton Quamby’s ultimate fate can be found in a report published in the Hobart Town Courier dated 18 March 1829. This was at the height of the Black Wars, in this part of the island waged between the Pallittorre people of the fertile Mole Creek and Meander fire-farmed plains and the British settlers pushing westwards in increasing numbers using the supply routes to the extensive land grants of the Van Diemen’s Land Company.

This extract is of particular significance in that it describes an attack by a group of Aborigines of whom “many … spoke good English but their words were extremely indecent … four men a woman and a black child were killed.” It is very likely that the murdered Aborigines included the English-speaking William Lyttleton Quamby, possibly wearing the stolen stock-keeper’s red coat, together with his extended family. As this report describes, the massacre took place at Bullock’s hunting ground at Nunamara, gateway to the picturesque St Patricks River valley, located between Mounts Barrow and Arthur.

As a result, the numbers of surviving Pallittorre were decimated.

In an ironic quirk of fate, Premier Peter Gutwein’s family settled at Nunamara on their arrival in Tasmania in the 1960s and it will fall to him to decide upon the possible placement of a prison at Quamby’s Brook with twenty per cent of its inmates of Aboriginal descent.

In the five years between 1827 and 1832 Malcolm Laing Smith, Police Magistrate for the Western Rivers, made a total of seventeen reports about Aborigines in his jurisdiction. In 1827 four stockmen were killed in separate incidents. This is a small number but a high percentage in terms of those working in such isolated locations. Between 1828 and 1831 thirteen separate incidents were reported, mainly robberies, and in two cases stockmen were assaulted or severely injured by Aborigines. 6

In March 1828, Governor Arthur informed the Colonial Secretary that ‘it is necessary that a military station should be permanently established in the vicinity of the Western [i.e. Meander] River [at Westbury]. This was part of the governor’s response to the escalating conflicts between white settlers and the Aboriginal inhabitants. 7

Henry Hellyer was a surveyor who explored most of the rugged North-West of Tasmania for his employer, the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Company), and wrote extensive journals and reports which are now held in various archives. Overall, it seems clear that Henry Hellyer accepted the VDL Company view that their royal charter from King George IV made the Aboriginal people of North-West Tasmania trespassers on company land.

In August 1830, while building a footbridge over the River Wey near its junction with the Hellyer River, Hellyer’s camp at Weybridge was visited by George Augustus Robinson with his ‘Friendly Mission’ whose intent was to investigate claims of killings, including the Cape Grim massacre by VDL Company employees, and to remove all Aboriginal people from their land then relocate them to an offshore island. The party who visited Hellyer’s camp included Truganini and her husband Wooredy.

In his diary entry for 12 August 1830 Robinson refers to Quamby as a freedom fighter when an unnamed person (probably Henry Hellyer) informed me of a stockkeeper called Paddy Heagon at the Retreat who had shot nineteen of the western natives with a swivel-gun charged with nails; and that a native named Quamby had disputed the land occupied by the whites and that he had successfully driven them off, but was he was afterwards killed with others. 8

The Retreat was a property on the outskirts of Deloraine granted to Hobart solicitor Galamiel Butler. Today the Ashley Youth Detention Centre is located on this property. It is remarkable that Hellyer gave Robinson the name of the aggressor, Heagon, that he knew about and could identify and name the Aborigine, Quamby, and also state that he was afterwards killed. Hellyer’s account concurs with the date and circumstances of Quamby’s death in March 1829 as reported in the Hobart Town Courier.

Lyndall Ryan in her ground-breaking book, The Aboriginal Tasmanians, refers to Quamby, a leader of the Pallittorre people, as being shot in the district in July 1830. 9 Lloyd Robson in his History of Tasmania, also repeats the story of the heroic Aboriginal resistance fighter, Quamby who disputed the land occupied by the colonists near Westbury. 10

Quamby’s memorials are the Brook and the Bluff which continue his name and respect his memory, for those who know his story.

John Hawkins has lived in Tasmania for 17 years. He has recreated with his wife Robyn a 19th century landscape over the Bentley Estate at Chudleigh. He is interested in the Tasmanian way of doing business. John was commissioned into the Diehards from Sandhurst in 1962.

- Alison Alexander, ‘Mathinna (c. 1835–?)’, People Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/mathinna-29655/text36623, accessed 19 March 2020.

- Keith Windshuttle, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History: volume one: Van Diemen’s Land 1803–1847 (2002). See also Windshuttle’s article in The Sydney Papers 2003, p. 24. http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/resources/pdfs/197.pdf.

- Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office, Hobart, registers of baptisms, RGD 32/1/1.

- A.W. Campbell, ‘Brumby, James (1771–1838)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/brumby-james-1840/text2125, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 29 March 2020.

- See TAHO, RGD36/1/1 for relevant registers of marriages.

- Murray Johnson and Ian McFarlane, Van Diemen’s Land: An Aboriginal History (2015), p. 125, 129.

- Nick Brodie, The Vandemonian War … (2017), p. 16-17.

- N.J.B. Plomley (ed.), Friendly Mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (1966), p. 197.

- Lyndall Ryan, The Aboriginal Tasmanians (1981).

- Lloyd Robson, A History of Tasmania, volume 1: Van Diemen’s Land from the earliest times to 1855 (1983).

JOHN HAWKINS: A Proposed Prison at Westbury – Introduction.

Brett Lucas

April 12, 2020 at 20:20

Thank you John, for the fascinating history of the area over 200 years.

I look forward to part 2 of your opinion piece to tie in with the relevance of the proposed Westbury prison.