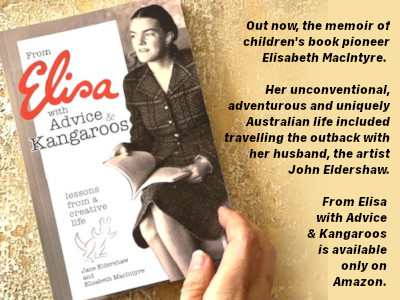

Behind the wire: Sue Neill-Fraser. Image Supplied

Andrew L. Urban:

In what acclaimed legal expert Dr Bob Moles describes (60 Minutes, 9 Network, Sunday, August 24, 2014) as the worst miscarriage of justice in 40 years, the 2010 murder conviction of Sue Neill-Fraser has now been fatally and forensically undermined with the latest report from the Victorian Police Forensic Services Department.

[ The Neill-Fraser case: In 2010, Sue Neill-Fraser was tried and convicted of the 2009 Australia Day murder of her partner Bob Chappell on board their yacht, Four Winds, anchored in Sandy Bay, Hobart. Chappell’s body has never been found, no murder weapon was produced at her trial, there were no eyewitnesses and there is no forensic evidence linking Neill-Fraser to the murder. ]

As explosive and far reaching as the finding of the legendary matinee jacket in the Lindy Chamberlain case 28 years ago, the DNA report confirms that a person other than the accused was present at the crime scene. (The accidental discovery of baby Azaria Chamberlain’s matinee jacket near a dingo lair well after Lindy had been tried, convicted and jailed, led within five days to her release from prison, as it was evidence supporting a key element of her defence.)

In Ms Neill-Fraser’s case, the investigating police and the DPP during the trial, as well as the subsequent appeal judges, all dismissed the DNA sample found on the yacht and its provenance, as being of no consequence, “a red herring” said the DPP, Mr Tim Ellis, since it was probably transferred on the shoe of a policeman, he suggested to the jury. He told the High Court that “The core evidence was … she [the homeless girl] was not on the boat” – and the High Court refused leave to appeal on that basis.

The DNA of a then homeless 16 year-old girl found on Four Winds on January 30, 2009, is now confirmed by Victorian Police Forensic Services Department to be of primary transfer in nature, contradicting the evidence she gave at trial saying she had never been on the boat. (Ms Neill-Fraser’s lawyer was unable to access the necessary materials to have new independent DNA tests carried out until the Coroner’s report was handed down early in 2014.)

This report contradicts the prosecution’s argument on the matter, it contradicts the Court of Criminal Appeal’s reasoning for refusing to uphold this ground of appeal, and it contradicts the High Court’s view that the matter was not on a substantial point.

Taken together with a litany of serious legal and other forensic errors at trial, this represents a catastrophic failure of the justice system, and if such an error is not urgently addressed, democracy itself suffers through the erosion of public confidence in what is one of the main pillars of our democratic system – a safe, reliable, self-correcting criminal justice process.

Referring to the new DNA report, Ms Neill-Fraser’s lawyer for the past two years, Ms Barbara Etter APM, says: “The conclusion has to be drawn that the DNA was deposited directly onto the deck of the yacht by the homeless girl. Given the girl’s constant denials about ever having been on the boat, this development presents a rational or reasonable alternative hypothesis which has not been excluded as to what may have happened to Bob Chappell on Australia Day 2009”.

In his closing (CT pp.1428 – 1461) defence counsel Mr Gunson SC repeatedly mentioned the Meaghan Vass DNA. He argued that transference was not credible and that the homeless girl was on board. It therefore followed logically that she could not be excluded as a rational hypothesis.

In the Appeal Court, Mr Gunson (at p93) again stressed the implications of the DNA: “To say that it’s completely speculative is just not open in my respectful submission. It’s quite the opposite, you’ve got a person whose DNA is there about whom there is evidence that she’s lied to the Court or may well have lied to the Court about her whereabouts on that night. It went not just to the possibility of an alternative suspect, it also went to the issue of whether or not this boat had been the subject of unlawful interference at earlier or later stages, because that was part of the appellant’s defence.

Andrew L. Urban has been a professional journalist for over 30 years and is currently publisher & editor of online publications pursuedemocracy.com and urbancinefile.com.au He has contributed over 2,000 freelance articles to mainstream media including The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald, Sun Herald, The Bulletin and many others.

Ben Lohberger:

The evidence at Susan Neill-Fraser’s trial speaks for itself.

While the original trial transcript is not available publicly, the Court of Criminal Appeal has published a transcript of its decision to throw out her appeal, and it makes for sobering reading (• Court of Criminal Appeals decision. Read for yourself, here )

Ms Neill-Fraser lied repeatedly about her whereabouts on the night of the murder. She lied about the deteriorating state of her relationship with Bob Chappell. She lied (to the first police officer she met) about criminals using the yacht for drug-smuggling, before it was even known that Bob Chappell was missing. She lied about her clothing on the night of the murder. She lied about injuries to her hand and wrist that occurred on the day of the murder. She lied about the reason Bob Chappell remained on the yacht on the day of the murder. She lied about leaving the dinghy tied up on the day of the murder. She lied about Bob Chappell’s ability to use the dinghy. She lied about the yacht being broken into in Hobart. She lied about the yacht being broken into in Queensland. She then lied about ever claiming that the yacht had been broken into in Queensland. And she repeatedly referred to Bob Chappell as if he were already dead, while being interviewed by police just one day after the yacht had been found sinking.

Her farrago of lies were clearly aimed at creating a scapegoat, and obstructing the police investigation into her own activity on the night of the murder. She is yet to provide a verifiable explanation for any of her deceptions, so we still don’t know what she was doing that night.

Her supporters claim she was ‘confused’ or ‘on drugs,’ and have resorted to picking over legal minutiae, or raising spurious legal issues that were dealt with during the trial, the appeal, the inquest, and the rejected application to the High Court. But the evidence continues to speak for itself.

The full transcript of the Court of Criminal Appeal decision is lengthy. I’ve included what I believe to be some of the most compelling findings below, findings that have been glossed over by Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters, with my own clarification added in [ ] brackets. For the full list of findings please visit http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/tas/TASCCA/2012/2.html

The appellant [Sue Neill-Fraser] and the deceased [Bob Chappell] purchased and took possession of the [yacht] Four Winds at Scarborough Marina in Queensland. There was evidence suggesting that they had spent more than they had originally planned.

They hired two crew members for the journey from Queensland to Hobart. They were Peter Stevenson and David Casson.

[Bob Chappell then suffered a series of serious nosebleeds, and was admitted to hospital before travelling back to Hobart independently. Sue Neill-Fraser subsequently sailed the yacht to Tasmania with the crew members, and was met by Bob Chappell following arrival in Hobart].

Evidence was given by Mr Stevenson that during the journey the appellant said that her relationship with the deceased was strained, it was over and it had been for some time. She also said that she would like to borrow $100,000 from her mother to buy out the deceased’s interest in the yacht.

Mr Stevenson’s evidence was that [when SNF arrived in Hobart with the yacht] the deceased “went to approach Sue and she really just stood back from him and ignored him, didn’t sort of respond to his – to, you know, acknowledging that – how he was”. He said that he had noticed no sign of affection between them when they were together on the boat.

Evidence was given by the deceased’s son, Timothy Chappell, that on 26 December 2008, and again two or three weeks later, he was on the Four Winds when the appellant and deceased were both present. He thought that “there was quite a lot of tension between them”, and said that he “felt a bit uncomfortable on the boat because of the tension between them”. He referred to sniping words and obvious friction between them. The source of it appeared to him to be that they had different expectations for what they would do with the yacht.

Evidence was given by Jeffrey Rowe, a Queensland yacht broker who negotiated the sale of the Four Winds to the appellant and the deceased. He said that in the course of a telephone conversation he had with the appellant on 8 January 2009, she told him that she and the deceased had separated and she commented “that she was just tired of having to do everything”.

[On the morning of 26 January 2009 Sue Neill-Fraser visited Bob Chappell on the yacht, before departing later that morning to attend a lunch appointment.]

The appellant drove home to Allison Street, changed and returned to the Royal Yacht Club with Ms Sanchez for lunch. At the club, Ms Sanchez took some photographs of the appellant. They showed that she had no injuries or strapping on her wrist.

[Sue Neill-Fraser then returned to the yacht mid-afternoon on the same day. She told police that she had an argument with Bob Chappell, who she said told her he wanted to stay on the yacht overnight, so she took the dinghy back to shore after about an hour she estimated (leaving him stranded on the yacht overnight)].

The appellant said to police that it was safer for her to leave the deceased on the yacht without the dinghy because he was not adept at getting in and out of it on his own.

However, his son, Timothy Chappell, gave evidence that the deceased was quite capable in the dinghy. Ms Sanchez’s evidence was that on 25 January 2009, the deceased showed the appellant how to use a new outboard motor on the dinghy. The deceased’s daughter, Katherine Chappell, gave evidence that when she went out to the Four Winds on 26 December 2008, the deceased operated the dinghy and the appellant criticised him concerning the way he was driving it into the waves. There was also evidence that the deceased controlled the dinghy containing him, the appellant and two men who were going out to work on the Four Winds in early January 2009.

The appellant said that when she returned from the Four Winds [that afternoon], she tied the dinghy to a ladder at the Royal Yacht Club in her usual way with three knots. She believed she had tied it up adequately and said that it had never come undone before.

At 9.17pm on 26 January 2009, the appellant made a 14 minute telephone call to her daughter, Emma Mills, on the landline at Allison Street. At 9.31pm she telephoned her mother for about five minutes. At 10.05pm she received a telephone call on the landline from Mr Richard King. The call lasted approximately 29 minutes.

The next telephone call to or from the Allison Street landline was at 3.08am on 27 January, when a *10# call was made from it. The function of such a call is to retrieve the number of the last unanswered telephone call to a landline service.

John Hughes gave evidence that between 11.30pm and midnight on 26 January, he was parked at the end of rowing sheds at Marieville Esplanade when he saw and heard an inflatable dinghy with an outboard on the back coming from the direction of the Royal Yacht Club, heading northeast towards the Eastern Shore of the Derwent. It was open to infer from that evidence that it was travelling roughly from where the appellant had said she left it at the Royal Yacht Club and roughly towards the Four Winds. Mr Hughes said that there was only one person in it who had the outline of a female, but he could not be definite. He was “almost 100 per cent definite” that there were no other persons in the area of the sheds.

At about 5.40am on 27 January, a witness found the dinghy bobbing against rocks. The witness secured it. With another man he headed out in a boat. As they passed the Four Winds they noticed that it was very low in the water on its mooring. They boarded it. Shortly after, the police arrived as a result of a call.

[The dinghy’s painter (the rope with which it was allegedly tied to the ladder)] was inside the dinghy, which suggests that it had been put there by someone and that it had not simply come undone from the ladder where she said she had tied it. If it had become undone with the result that the dinghy drifted away, it is likely that the painter would have been trailing in the water.

At 7.04am, on 27 January 2009, an unanswered telephone call was made from the landline at Allison Street to the appellant’s mobile telephone which was later found on the Four Winds. No further call was made by the appellant to that telephone and she raised no alarm. Having received reports of the Four Winds sinking, police telephoned her on the landline at Allison Street at 7.11am. She headed directly to Marieville Esplanade in the car. Her evidence was that she had parked it overnight outside the house.

On the shore at Marieville Esplanade, before it was known that the deceased was missing, she spoke with Constable Shane Etherington. She told him that the deceased had been on the yacht making some repairs in relation to some panels that had apparently been loosened by unknown persons. She said that she believed the boat may have been boarded in the two or three days prior to the deceased being on it. She explained that a similar yacht had been used to smuggle drugs into Australia from other countries and the drugs were stashed in similar panels and she believed that was what may have happened to the Four Winds. She asked if the police had sniffer dogs which could go onto the yacht.

That morning, a red jacket was found on a brick wall outside 2 Margaret Street by the occupant. It was about 120 metres from where the appellant said she had left the dinghy tied up on 26 January. The occupant had not seen it there when he arrived home the previous evening at about 6pm. A police officer took possession of it and it was placed in the boot of a police car at Marieville Esplanade. It was shown to the appellant who said that it did not belong to her and she had never seen it before. However, a swab taken from the inner surfaces of the collar and cuffs of the jacket was found to contain a DNA profile that matched her DNA profile and the chances of some other unrelated person matching it was less than one in 100 million.

When the appellant was at Marieville Esplanade that morning, police officers observed that she had some strapping round her wrist and a Band-Aid on her left thumb. She said she had cut her thumb. At the request of Constable Stockdale she removed the Band-Aid and revealed a one to two centimetre cut. In the course of the conversation she said that her fingerprints might be on a torch on the Four Winds. A torch was indeed found on the Four Winds. It had human blood splattered on it and a DNA analysis of the blood matched the DNA profile of the deceased.

When police boarded the Four Winds that morning they noticed blood on steps, a knife on the floor of the wheelhouse and the torch with blood on it and no trace of the deceased. The yacht was low in the water and sinking. The causes were located. A pipe to the for’ard toilet had been cut allowing seawater to flow in. It was also discovered that a seacock under the flooring in the for’ard part of the yacht had been opened, allowing seawater to flow in.

Evidence was given by Constable Lawler, who had experience in marine and rescue services and with water craft, that in his opinion the person responsible for cutting the pipe and opening the seacock had an intimate knowledge of the Four Winds. That was particularly the case with the seacock, which was under a carpet and panel, and which served no apparent purpose.

The operation of the plumbing aboard the Four Winds, including the location of the cut pipe and the seacock, had been explained to the appellant by a plumber, Mr Klaas Ruiter, when working on the yacht in Queensland. A photograph in evidence showed her with the book open at the plumbing diagram. Evidence from Mr Nathan Krokowiak, a mechanical fitter who worked on the yacht on or about 15 January 2009, was that he explained to her about “gate valves, seacocks and things like that which are open to the outside of the vessel” whilst working on the area containing the seacock which was found on 27 January to have been opened.

The inflatable dinghy had many areas that were positive to luminol, a screening test for blood but not a conclusive one.

Sergeant Conroy also gave evidence that the appellant drew attention to some rub marks on the wooden surrounds of the main hatch for entry into the yacht, which she said had not been there before. The Crown maintained that the marks were small and inconspicuous. There were fibres in the marks that appeared consistent with those from a rope.

It was also Sergeant Conroy’s evidence that when speaking to the appellant on 28 January, at which time he obtained a statutory declaration from her, she referred to the deceased throughout in the past tense, although at one time she apologised, saying that she and the family had come to the realisation that he was dead.

In the days following 27 January she told Timothy Chappell that she had been to Bunnings the afternoon before.

On 28 January 2009 she made a statutory declaration in which she said that after tying up the dinghy at the Royal Yacht Club she went to Bunnings for a long time, although she did not buy anything, just browsed. It was starting to get dark when she arrived home. She mentioned the telephone calls she made and received and said she got off the telephone at 10.30pm. That accorded with records. She said that she stayed alone at home that night and that the following morning she was notified the yacht was sinking. She made no mention of travelling to Marieville Esplanade after 10.30pm.

On 5 February 2009, she told Constable Marissa Milazzo and Detective Senior Constable Shane Sinnitt that after she left the Four Winds on 26 January she went straight out to Bunnings. [She then gave detailed evidence about her clothing on the day and her movements around the shop].

When interviewed by police on 4 March 2009, she continued to maintain that she drove to Bunnings from the Yacht Club. She said she remembered feeling guilty when doing so because she thought that if the deceased telephoned her, he had her mobile and she was not at home. However, she was aware that police had examined CCTV footage at Bunnings and could not find her on it and retreated to claiming that she was “pretty sure” she had gone there. She was told that Bunnings shut that day at 6pm, which made it unlikely that she could have been there for “hours” as she had previously claimed.

Later in that interview she maintained that she did not leave her home on the night of 26 January after receiving the telephone call from Mr King.

On 5 March 2009, Detective Sergeant Conroy spoke to the appellant’s two daughters about the investigation and showed them a photograph taken by a camera at the corner of Sandy Bay Road and King Street, Sandy Bay, at 12.15am on 27 January 2009, which showed a grey station wagon similar to the appellant’s vehicle travelling on Sandy Bay Road. The appellant’s daughters were in constant contact with her.

Ms Sanchez gave evidence that on either 8 or 10 March 2009, she had a telephone conversation with the appellant, in the course of which the appellant told her that on the night of 26 January she was disturbed or anxious about the content of the telephone call from Richard King and had driven down to Sandy Bay, looked across at the yacht, but it was in darkness, and then drove back. That was the first occasion upon which the appellant had admitted to returning to Marieville Esplanade that night.

On 13 March 2009, she was interviewed by an ABC journalist, Ms Felicity Ogilvie. She told Ms Ogilvie that after the telephone call from Mr King she drove down to the boat to check that everything was okay, did not see anything going on at the yacht and drove home. She added that she saw homeless people with fires while down there. Ms Ogilvie later provided that information to police. It was the first time they were aware that the appellant had returned to Marieville Esplanade on the night in question.

On 23 March 2009, Ms Sanchez had another telephone conversation with the appellant in which the appellant said that although she had driven down to Marieville Esplanade that night, she left the car there and walked back home to West Hobart for the exercise. It was the first time she said she had left the car at Marieville Esplanade.

Police interviewed her again on 5 May 2009. Asked about what she had done on the afternoon of 26 January after going out to the Four Winds, she said that she had been mistaken about going to Bunnings, claiming that she had mixed up the day with another day a few days earlier when she had left the deceased on board the yacht and gone to the store.

During the same interview, she said she had been on the yacht on the afternoon of 26 January until later than she had previously indicated, and after tying the dinghy at the Royal Yacht Club, she walked back to Allison Street, West Hobart, leaving the car on Marieville Esplanade or around the corner in Margaret Street, she could not remember which. She said she did not remember whether it was daylight or dark. After the telephone call from Mr King, the content of which had unnerved her, she decided to collect the car and drive it home so that it would be available to her to drive to the yacht if the deceased called her. She decided not to telephone him because having regard to the lateness of the hour, he might be asleep. So she walked to the car at or near Marieville Esplanade. However, on arriving there she found she had farm keys and not the car keys and had to walk back to Allison Street to collect them and return once again to the car. She then drove along to the rowing sheds, which was the only place from which the boat could be seen properly. She got out, walked down to the beach and saw a fire going and homeless people there. She could not see the boat because it was pitch black. She felt a lot better for having gone there. She then drove home.

In that interview, the appellant was told that the red jacket police had shown her on the morning of 27 January was in fact hers because it contained her DNA. She conceded it was hers and said she had no idea how it came to be on the fence in Margaret Street.

She agreed in the interview that when on 27 January she gave an account to police of her movements the night before, she had not told them about returning to Marieville Esplanade. She gave as her reason that she was worried Timothy Chappell would be upset at mention of her concern about the subject of the telephone conversation from Mr King.

She also told the police that when the yacht was being repaired at Scarborough Marina in Queensland, the mechanic, Mr McKinnon, advised her that it had been illegally entered and panels had been opened and things moved about.

It was Timothy Chappell’s evidence that on 27 January the appellant told him that the yacht had been broken into twice in Hobart on its mooring, which surprised him because he had not heard about it before. The appellant told Constable Etherington on 27 January that the Four Winds may have been boarded two or three times before, that some panels had been removed by unknown persons, and that the yacht may have been used to smuggle drugs. On the same day, she made a statement in which she said that approximately 13 days before she and the deceased discovered that someone had been on the yacht unlawfully. She noticed that the chart table had been accessed and the freshwater pump cover and the electrical switchboard had been opened. She said exactly the same thing happened in Queensland in October when someone had been on the boat.

A marine mechanic, Mr James McKinnon, gave evidence that the appellant and the deceased commissioned him to inspect the Four Winds in Queensland and to work on it at Scarborough Marina. During the course of the work he reported to the appellant that he believed someone had been entering the yacht after he finished work some days, and he also told her that on one occasion he noticed an electrical panel had been removed. However, he subsequently discovered that an electrician, Chris Geddes, had done that and he told the appellant that was the case. Evidence was also given by Mr Rowe that he had also discussed with the appellant about the electrical panel having been opened and about the situation that people thought the boat was being broken into. He said it was discovered that an electrician had been working on the switchboard of the yacht and he informed the appellant of that.

That evidence of Mr McKinnon and Mr Rowe was not challenged by the appellant’s counsel in cross-examination. However, the appellant gave evidence that it was she who told them that it was Mr Geddes who had entered the yacht.

On 27 January 2009 the appellant told Sergeant Conroy that Four Winds had been entered on two occasions, that it appeared to her that something heavy may have been lifted out, and she believed it was drug smugglers and that the deceased may have been on the yacht when they came back to it.

On 13 February 2009, in a telephone conversation, the appellant told Sergeant Conroy again about break-ins on the vessel. On 19 February she mentioned her belief that the prefix PV in the registration number of the yacht stood for Port Vila, and that drugs smugglers from Europe went to Port Vila and that was a line of inquiry she thought he should follow.

In the course of being interviewed on 5 May 2009, the appellant denied that there had been any break-ins on the yacht in Queensland or Tasmania and she denied saying that it had been searched.

When giving evidence, the appellant said that she and the deceased went aboard the Four Winds on 10 January 2009 and found it had been entered and searched, with floor hatches pulled up, cupboard doors open, some of the cushions unzipped and mattresses flicked up, but there was no damage and nothing was missing. They decided between them not to report the matter to police. Later in evidence she denied ever saying that the yacht had been broken into in Queensland.

Other circumstantial evidence relied on by the Crown included the evidence of Mr Phillip Triffett. He gave evidence that he and his partner had been friends with the appellant and the deceased some years before, and that the appellant owned a yacht at that time which she kept at a marina down Electrona or Margate way. He said that when they were on the yacht in about 1996 or 1997, the appellant asked him to assist her in taking her brother Patrick out to sea and throwing him overboard, because he was in her way over their mother’s property. She said they would weigh him down with a toolbox and that Mr Triffett would then take the yacht closer to shore and sink it after she had gone ashore in the dinghy. She showed him how they could sink the yacht by using the bilge pump.

Mr Triffett also gave evidence of a conversation not long after at the appellant’s home when the appellant complained that the deceased was mean with his money and “dangerous around the kids” and she said he had to go. She wanted the same thing to happen as she had suggested before, except that she wanted the deceased to be wrapped in chicken wire.

Ben Lohberger grew up in southern Tasmania and lives in Glen Huon, where he’s currently working on his house and farm. He has previously worked for a range of employers including the Department of Social Security, Media Monitors, the Premiers Office, the Tasmanian Greens, Aurora Energy, and The Parthenon (No IV).

• Eve Ash, in Comments: Anyone who missed 60 Minutes 24 August and the new evidence, new leads, and problems with the forensic science in the case …

• Ben Lohberger, in Comments: Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters appear to have access to the transcript of Ms Neill-Fraser’s trial, a transcript that is not available publicly. If they are going to cherrypick …

Ben Lohberger

August 24, 2014 at 17:50

Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters appear to have access to the transcript of Ms Neill-Fraser’s trial, a transcript that is not available publicly.

If they are going to cherrypick quotes from that transcript to support their own case, as above, then they should publish the entire document so we can all see what happened during the entire trial, not just the parts they wish to highlight.

davies

August 24, 2014 at 17:54

Thank you Mr Lohberger. Puts it all into perspective.

Eve Ash

August 24, 2014 at 19:24

It was not the fault of the jury in this case! They were misled by inadmissible evidence, mistakes by the DPP and judge, and now we have NEW DNA EVIDENCE – from Victorian Police Forensic Services Department (VPFSD). REF: http://www.betterconsult.com.au/blog/suggestions-from-tasmania-police-about-the-vass-dna/

“No innocent or reasonable explanation for Meaghan Vass’ DNA on the deck of the yacht! Contrary to DPP theory in the Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeal & High Court.”

Eve Ash

August 24, 2014 at 19:25

Please consider the Tasmanian Coroner’s Comments in Relation to Meaghan Vass and the DNA issue Concerning the Death of Bob Chappellhttp://www.betterconsult.com.au/blog/the-tasmanian-coroner-s-comments-in-relation-to-meaghan-vass-and-the-dna-issue-concerning-the-death-of-bob-chappell/

Eve Ash

August 24, 2014 at 19:39

Anyone who missed 60 Minutes 24 August and the new evidence, new leads, and problems with the forensic science in the case: http://www.jump-in.com.au/show/60minutes/stories/2014/august/justice-overboard/ MeaghanVass’DNA was on the boat. Bob Moles says this miscarriage of justice is the worst of the worst.

http://www.jump-in.com.au/show/60minutes/extraminutes/3745973716001/

Steve

August 24, 2014 at 20:14

Thanks for putting the alternative view forward Ben. It’s nice to see the other side of the argument.

What I struggle with though is to see how the list you have produced demonstrates evidence of murder? I can see how, combined with some good solid physical evidence, such a list could flesh out a circumstantial case, but you appear to be attempting to make bricks with straw alone.

The dinghy luminol test is a good example. One of the very few pieces of actual physical evidence. Inflatables are not easily cleaned, the nature of their construction leaves lots of tiny crevices. The prosecution case revolves around a dinghy splattered in blood and yet all they could produce was a preliminary test that the defence have subsequently torn to bits?

I certainly don’t blame the jury. A list such as yours, backed up by an experienced prosecution putting forward an apparently plausible, but speculative scenario, could be quite convincing. I feel the judge failed in his role. It should have been made very very clear what was speculation and the solid facts (such as they were) should have been separated out and held up for examination.

Ben, if you go through your list and pull out all the facts, you’ll find there’s not many. A few phone calls, a dinghy where it shouldn’t be, a jacket, some CCTV footage, a sinking yacht. Do really think that they are sufficient to enable you to say “This is what happened. There is no other possible explanation.”?

john hayward

August 24, 2014 at 22:25

I would be fascinated at the judge’s instructions to the jury. Same goes for those to Bryan’s jury.

John Hayward

Barbara Mitchell

August 24, 2014 at 23:23

Mr Lohberger, Sue Neill-Fraser was tried for MURDER, and the resulting conviction means her FREEDOM has been foregone for a minimum period of 13 years. This was not a traffic offence with a fine attached.

Before the state imprisons a person on such a charge, a jury of their peers must be convinced BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT of their guilt. If the evidence is entirely circumstantial, the jury must be further convinced that there is NO reasonable explanation for the circumstances of the alleged crime other than the guilt of the accused.

In the case at hand, there are several reasonable alternative explanations. For example, there is the third person DNA found on the yacht and later identified as belonging to Meaghan Vass – a person whose whereabouts at the time of the alleged offence have not been accounted for. Being homeless at the time, perhaps she decided to spend a night on one of the empty yachts moored off Marieville Esplanade. Maybe Mr Chappell surprised her, there was a confrontation and he fell overboard. Despite the DPP’s skepticism, this is not an unreasonable scenario.

In fact, it makes more sense than the DPP’s version of events – a woman in her fifties killing her partner in a premeditated attack with a wrench and then winching his weighted body over the side of the yacht into a tender and disposing of it into the Derwent, for no apparent reason. Unless you have forgotten, there is NO evidence to support this proposal – no weighted body and no wrench.

Ms Vass denied having been on the yacht, and this was apparently accepted without question. So, how did her primary DNA get there? Why was a homeless girl who was known to have lied several times about her whereabouts believed implicitly? Especially considering that so much has been made of Sue Neill-Fraser’s ‘farrago of lies’ (what is a farrago, by the way?).

And, how is it possible to reconcile the evidence– I believe it was an ATM camera image, which would have been time stamped – that Ms Neill-Fraser was travelling on Sandy Bay Road, approximately five minutes from Marieville Esplanade, at 12.15, with the sighting of a woman, taken to be the accused, motoring towards the Four Winds in a tender between 11.30 pm and midnight?

If she was heading towards Marieville Esplanade, then the evidence of Mr Hughes, who testified that he saw a woman heading towards the yacht at that time, is clearly inaccurate. It would take a person at least 15 to 20 minutes to reach Marieville Esplanade, park a car, walk to the point where the dinghy was tied, start the motor and commence moving away into the river, making it more like 12.30 to 12.45 than 11.30 when Ms Neill-Fraser was allegedly doing this.

If she was travelling away from Marieville Esplanade, then she must have managed to board the yacht, dispose of Mr Chappell’s body in the manner postulated by the DPP and return to shore in a matter of minutes. If this is the case, did Mr Hughes observe the alleged activity and see her return to shore, or did he immediately leave the vicinity after making the observation relied on by the DPP?

And what about the red jacket left on the fence in Margaret Street? Was it a particularly unique jacket? If it wasn’t, it is quite reasonable for Ms Neill-Fraser to say it wasn’t hers if she didn’t put it there. Perhaps some other person who had been aboard the Four Winds took it from the yacht and dumped it where it was found. More importantly, why would a cool calculating killer, as Ms Neill-Fraser was portrayed, leave an item of their clothing in plain sight in an unexplained location near the scene of an alleged crime?

The ‘callback’ phone call made by Ms Neill-Fraser at 3.08 am on 27 January is also mentioned as part of the circumstantial evidence against the accused. Why? How is it relevant to her guilt or otherwise? Maybe she awoke and decided to check if Mr Chappell had called. Maybe she didn’t call him directly because she didn’t want to wake him. All perfectly reasonable. And if she had already dispatched Mr Chappell, as the DPP’s scenario suggests, why would she bother to check if he had called? Was she asked about this call at trial?

The far more interesting call is the lengthy phone communication from Mr King at 10.30 pm. Why do we know virtually nothing about that call, except that it ‘unnerved’ Ms Neill-Fraser? Was the trial jury privy to any evidence about this call?

And, given the massive public interest in this case, why hasn’t the trial transcript been made available?

Barbara Mitchell

August 24, 2014 at 23:25

continued…

Mr Lohberger, you say that Ms Neill-Fraser’s ‘farrago of lies were clearly aimed at creating a scapegoat’. Who would this scapegoat have been? Someone in particular, or just anyone other than her?

You also assert that her supporters are raising ‘spurious legal issues’, but there is nothing spurious or inconsequential about a clearly unsafe conviction. We rely on a system that affords justice to all according to a centuries old ethos. The state cannot just make stuff up to secure a conviction because they ‘know’, despite the absence of any reliable evidence, that a person is guilty.

So many questions. So much REASONABLE DOUBT.

John Taylor

August 25, 2014 at 00:53

I watched 60 Minutes. Thank you to Charles Woolley and the the team for going down and doing the story – – I have not seen investigative journalism of that quality since Mike Moore headed up Frontline at the ABC.

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 02:49

The Luminol

The Luminol in the dinghy is one of a number of spurious legal issues being raised by Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters, who allege the jury was misled by the Luminol evidence because it is not a conclusive test for the presence of blood.

But the deficiences with Luminol *were* aired during the trial, where it was made clear during evidence that Luminol can produce a false positive for blood.

The Appeal Court also noted this deficiency with Luminol, stating in it’s findings that “[t]he inflatable dinghy had many areas that were positive to luminol, a screening test for blood but not a conclusive one.”

So this is not new evidence. The jury were well aware that Luminol can produce a false positive for blood, and the Appeal Court also considered that fact in their findings.

Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters appear to have access to the trial transcript, so maybe they could reveal *all* of the evidence in which Luminol and its shortcomings were discussed?

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 02:54

The homeless girl and her DNA

This is another spurious legal issue, and again it is one that received lengthy hearings in Susan Neill-Fraser’s trial, the Court of Criminal Appeal, and the application to appeal to the High Court.

The DNA of a homeless girl was discovered in one spot on the deck of the yacht, three days after it was found sinking.

The girl was called as a witness in the trial, and gave evidence that she had no idea how her DNA got on the yacht. She said she did not remember ever being on the yacht while it was moored, or after police had placed it a private slip at Goodwood for inspection.

She was grilled by Susan Neill-Fraser’s lawyer, who was at one stage described by the Court of Criminal Appeal as “unfair” in his cross-examination regarding the homeless girl’s exact address at the time of the murder.

She revealed during her evidence that she was 15, had been homeless since she was 13, and had difficulty remembering many things, including her exact location on the night of the murder (21 months earlier).

She finished giving evidence and was dismissed, before the defence lawyer decided he wanted to recall her.

After legal debate, the judge denied the request because he felt there was zero prospect of anything further coming from the witness, given that she didn’t remember ever being on the yacht, or exactly where she was on the night of the murder.

The Court of Criminal Appeal and the High Court both agreed with the judge’s ruling:

The trial judge refused the recall request as following “but the question of just where [the homeless girl] was and what she did on the night of the 26th of January seems to be peripheral when her version of events is unshakeably, or apparently unshakeably, that she did not go onto the Four Winds, that she didn’t go to the slip yard at Goodwood and that she didn’t go to Constitution Dock at or about the time that the boat was there.”

The Court of Criminal Appeal found that “[t]he appellant has failed to establish that there is a significant possibility, one greater than a merely speculative one, that the jury would have acquitted her if [the homeless girl] had been recalled. It cannot be concluded that the verdict was unsafe or unsatisfactory, or that a miscarriage of justice resulted”.

The High Court found “… in our view, this application does not give rise to a question suitable to a grant of special leave as the applicant has not shown that she was denied an opportunity to produce evidence on a point of substance which can be shown to have had a significant possibility of affecting the jury’s verdictâ€.

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 02:58

60 Minutes and the homeless girl’s DNA

Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters have now used 60 Minutes to unveil yet another red herring – new DNA analysis that asserts the homeless girl’s DNA could not have been transferred second-hand onto the yacht via “foot traffic on the deck”.

But expert evidence given at the trial established that the homeless girl’s DNA could have been transferred onto the yacht by foot traffic, or by any other means. The Appellate Court summarised this evidence as follows:

“Its presence [the homeless girl’s DNA] on a walkway could be accounted for by a lot of people passing over the area and one of them transferring onto the walkway the DNA of a person picked up elsewhere on the bottom of their shoe. Potentially anything could be carrying a person’s DNA and could transfer it.”

Barbara Etter presented this new DNA analysis on this week’s 60 Minutes. Given that Ms Etter appears to have access to the trial transcript, and definitely has access to the appeal transcript, you’d think she already knows that the court didn’t rely on “foot traffic” alone as the only potential source of the DNA transfer. Interesting that she failed to mention it.

But I will mention something now. The 60 Minutes segment included a tabloid hatchet-job on the homeless girl that was nauseating, and completely unnecessary. I’ve warned about the behavior of Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters previously, and pointed out their willingness to blacken anyone and everyone’s name in their crusade, but this was particularly repellent.

Rosemary

August 25, 2014 at 03:13

8 hours of interviews with police would produce a lot of information. Going by that long list of things that you have said are lies,( plenty of cherry picking in that lot) then one would suppose then the missing fire extinguisher relied upon so heavily is a lie too. Basically it all just doesnt add up or make sense how the prosecution has strung it together. Mr. Chappell was a strong swimmer, so just as plausible would be that the fire extinguisher was used as a flotation device and he swam away to parts unknown.

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 06:25

The words of Justice Blow (1)

In January this year Andrew Urban wrote an article for TasmanianTimes that led to confusion about the judge’s remarks to the jury, not least amongst his fellow supporters of Susan Neill-Fraser.

[ http://oldtt.pixelkey.biz/index.php?/article/sue-neill-fraser-the-sentencing-blow-by-blow/ ]

The article criticised the sentencing remarks of the trial judge, Justice Blow, which were made after Ms Neill-Fraser had been found guilty by the jury.

Despite the Justice Blow’s remarks being made after the guilty verdict, Mr Urban criticised his “willingness to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt on matters which are quite evidently in doubt”. Amongst many other things.

Mr Urban was seemingly confusing the judge’s sentencing remarks, given after the verdict, with the judge’s directions to the jury, which are given *before* the verdict is reached.

I say ‘seemingly’ because Mr Urban quoted almost an entire paragraph of the judge’s sentencing remarks in his article, but strangely omitted the very first sentence of that paragraph, which read:

“For sentencing purposes, it is appropriate that I make findings as to how, when and why the crime of murder was committed, to the extent that the evidence enables me to do so.”

Mr Urban also supplied a link in his article, but it goes through to a menu page that contains another copy of his same article; it does not link the actual sentencing remarks.

Mr Urban’s quote of the paragraph of Justice Blow’s sentencing remarks:

I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Ms Neill-Fraser attacked Mr Chappell on board their yacht, the Four Winds, which was at its mooring off Marieville Esplanade, Sandy Bay. The attack occurred in either the saloon or the wheelhouse, out of public view, when the couple were alone. Mr Chappell probably died on board the yacht, but I cannot rule out the possibility that the attack left him deeply unconscious, and that drowning was the cause of death. I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Ms Neill-Fraser used the ropes and winches on the yacht to lift Mr Chappell’s body onto the deck; that she manoeuvred his body into the yacht’s tender …

The actual paragraph of Justice Blow’s sentencing remarks:

For sentencing purposes, it is appropriate that I make findings as to how, when and why the crime of murder was committed, to the extent that the evidence enables me to do so. I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Ms Neill-Fraser attacked Mr Chappell on board the yacht, the Four Winds, which was at its mooring of Marieville Esplanade, Sandy Bay. The attack occurred in either the saloon or the wheelhouse, out of public view, when the couple were alone. Mr Chappell probably died on board the yacht, but I cannot rule out the possibility that the attack left him deeply unconscious, and that that drowning was the cause of death. I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Ms Neill-Fraser used the ropes and winches on the yacht to lift Mr Chappell’s body onto the deck; that she manoeuvred his body into the yacht’s tender, …

[‘The trial of Ms Neill-Fraser for Murder,’ http://www.magistratescourt.tas.gov.au/decisions/coronial_findings/c/chappell,_robert_adrian_-_2014_tascd_04 ]

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 06:49

The words of Justice Blow (2)

Justice Blow’s actual directions to the jury have been published on the website of Mr Urban’s fellow Neill-Fraser supporter, Dr Bob Moles. The required password is ‘supreme’

[ http://netk.net.au/Tasmania/Neill-Fraser1.pdf ]

It’s a lengthy read at 63 pages, but a number of the directions completely undermine the claims of Susan Neill-Fraser’s supporters, especially that the judge somehow stitched her up while directing the jury:

– Although I’m the judge of the law the twelve of you are the judges of the facts, as I – I think I said this on day one; it’s your role to consider all of the evidence concerning the facts and where possible to reach conclusions or make findings about the facts. That area is yours alone.

– It’s also up to you, as the judges of the facts, to make some assessment of the witnesses and of the reliability or otherwise of the different witnesses and the different things that the witnesses have said. It’s up to you to decide which witnesses you think are mistaken, evasive, unreliable or dishonest. And for that matter, it’s up to you to decide how much reliance you place on the exhibits.

– Mr Ellis, in – at the end of his cross-examination of Ms Neill-Fraser, put to her a series of propositions as to, for example, the killing of Mr Chappell with a wrench, and she denied that. Well what he said, the suggested facts contained in his question, aren’t evidence. They’re a theory; they’re a theory that you ought to consider. But what the witness – when Ms Neill-Fraser said, “No, that didn’t happen,” her evidence is “No, that didn’t happen” – it’s your role to consider whether you accept it or not.

– In other words luminol which reacts positively to blood but also gives false positive results did produce a positive reaction in area 11, so maybe there was blood there, maybe the luminol was reacting to something else.

– And he [DNA profiler Mr Carl Grosser] was asked about a walkway. He said: “It’s a possibility. Logically on a walkway you’re going to get a lot of people passing over that particular area and potentially the mechanism for that sort of transfer to occur could be on the bottom of someone’s shoe or something like that. You could step in something and transfer DNA that way, that’s sort of logically what goes through my head, but again it’s speculation, I can’t say categorically that that’s what’s happening in this case.” Well I’d suggest you think about that.

gavin Collier

August 25, 2014 at 11:04

An innocent person has no need to lie. It is unfortunate our Courts have lost their veracity and our Police their integrity, worst of all is when the public is divided by doubts extracted incompletely from a clearly dishonest accused. I appeal to the supporters group to let this rest the deeper you dig the dirtier you get, give your support to those who have been incarcerated by being ignorant of the Law and fail to get reasonable representation and are from a poorer social demographic.

john hayward

August 25, 2014 at 12:34

Having observed character evidence from both the judge and prosecutor in this case in a civil case thirteen years before, my perspective on the SNF judgment is distinctly sceptical.

John Hayward

Rosemary

August 25, 2014 at 13:08

Reading Ben’s quote of expert dna at trial ” could” was the word concerning dna transfer by shoe, versus victorian police forensics say it is definitely “primary” DNA. There is a big difference that cannot be ignored.

Steve

August 25, 2014 at 13:34

#16; Thanks for that link Ben. I haven’t had time to read the full transcript but so far I’ve seen nothing that undermines my opinion. I would like somehow to be able to read it with an entirely open mind as it’s quite possible that I am biased, but when I read it, I detect a underlying message of “this woman is guilty but we must be seen to give her a fair trial”.

With regard to the DNA, as I understand it, the expert witness at the trial was asked whether the DNA could have been transferred to the site on the sole of a shoe. He said it’s a possibility. What else could he say in the circumstance, unless he was absolutely positive that it couldn’t have happened? Expert witnesses have to be very careful and it’s extremely difficult to prove a negative.

To dismiss that DNA, the prosecution should have had to have gone into the matter a lot more deeply, rather than simply getting a possibility from an expert witness. Without the DNA being conclusively dismissed, there was another possible scenario alive and well. The judge makes much of the ambiguity of the expert witness but doesn’t make much of the consequences of an alternative scenario in a circumstantial case.

I note the judge quotes an example of a child on a bike (P14), where a child is seen riding by, there’s the sound of the crash and the child reappears injured. This case is more along the lines of noting the child’s bike is missing and the child has a bruised knee. From this concluding the child was riding with no hands (because children often do this and someone heard your child talk about it a year ago), they crashed the bike and have now thrown it in the river to hide the evidence.

Steve

August 25, 2014 at 14:06

#11; I hate commenting after myself but realised I hadn’t responded to this one.

No problem with the deficiencies of Luminol, it gives an possible indication of blood. It’s a preliminary test.

My problem is the apparent lack of follow up tests. It appears inconceivable that there was no more testing done on the dinghy, other than a quick and dirty preliminary test. Had the prosecution been able to locate traces of Bob Chappell’s blood in the dinghy, it would have been an important part of their case. As one who’s had to clean fish blood out of an inflatable, it’s not an easy task without tipping it up and hosing!

Was there other testing done on the dinghy? No-one seems to mention the results.

Barbara Mitchell

August 25, 2014 at 14:49

# 16 ‘Mr Ellis, in – at the end of his cross-examination of Ms Neill-Fraser, put to her a series of propositions as to, for example, the killing of Mr Chappell with a wrench, and she denied that. Well what he said, the suggested facts contained in his question, aren’t evidence. They’re a theory; they’re a theory that you ought to consider.’

Seriously? Justice Blow was ‘directing’ – a I use the word loosely – a group of 12 lay persons, who had been exposed to almost two years worth of Tasmanian press coverage of the Neill-Fraser case, between the time of the alleged offence in January 2009 and the trial in October 20120. He told them that the DPP’s propositions regarding the commission of the alleged murder by Ms Neill-Fraser were not evidence, but they were ‘suggested FACTS’ – isn’t that a classic oxymoron? How can ‘suggestions’ be ‘facts’? Then he follows by noting that these propositions – that he has already told a jury of persons totally unfamiliar with legal protocols are ‘facts’ – are theories ‘THAT THEY OUGHT TO CONSIDER’.

He should have told the jury that the scenario described, was nothing more than speculation. That there was NO evidence to support it.

(Edited)

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 15:44

#20 No worries Steve.

The new DNA analysis changes nothing from the evidence given at the trial. There was a trace of DNA from another person found on the deck of the yacht, that person has no idea how it got there and denies ever being anywhere near the yacht.

There is no evidence to link that person to the yacht, apart from the trace of DNA, and (despite the misleading claims of a number of people) the DNA could still have been transferred second-hand to the yacht by any number of means apart from foot traffic.

The problem I have with the new analysis is that Ms Neill-Fraser’s supporters are falsely claiming it completely debunks the DNA evidence given at the trial. It does not. It changes nothing.

#21

I only brought up the Luminol because (again) Ms Neill-Fraser’s supporters were being misleading by saying the jury wasn’t told that Luminol sometimes provides false negatives for blood. The jury of course were told this.

Apart from that, the issue is yet another red herring.

The blood (or Luminol) in the dinghy were not even mentioned by Justice Blow in his directions to the jury.

It did not play a role in Sue Neill-Fraser’s conviction.

What it does do for me however, is confirm a pattern of behavior in some of those seeking to free the Ms Neill-Fraser.

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 16:09

#22

The judge made it abundantly clear that the scenario put by the DPP was a “theory,” “a series of propositions,” and that it wasn’t “evidence”. He did not tell the jury they were “facts” as you assert, he said “suggested facts”.

You also seem to be suggesting that the jury were influenced by press coverage prior to the trial. If you have any evidence of this new “theory” (“proposition”?), then you should provide it.

Geraldine Allan

August 25, 2014 at 16:37

#20 Steve, a “possibility” is much weaker speculation than probability, in my view. Then even a probability is not confirmation; still hypothesis.

Geraldine Allan

August 25, 2014 at 16:54

#22. Having three times been empanelled on a jury, I can assure you that the randomly selected 12 persons are not necessarily 12 skilled and scholarly persons, capable of recalling most of the evidence through the witness box, the judge’s directions and then forming a verdict based on those.

Based on my observations / experience, rather and often there are scant notes taken by some, others are confused with evidence, others have no understanding that the ‘expert’ witness is more often than not a “hired-gunâ€, and others fail to (i) comprehend, and (ii) pay any attention to, their obligations to and the importance of, “beyond reasonable doubt†verdict.

I could go on and I would like to, but it is a no, no and I would be prosecuted! Jury members are prevented from speaking about what happened inside the jury room. What I can say is that if they were able to speak out, I speculate that flawed system would be immediately reviewed and / or abolished.

Any onlooker that holds the opinion that the system is fair and perfect is misguided. I affirm that wrongdoing occurs inside the jury room; I’ve witnessed it. To say it is the best we’ve got, is insufficient when it gives rise to the probability that innocent persons can be convicted of a crime that they did not commit.

Eve Ash

August 25, 2014 at 17:47

Just for the record at the very end of the trial, before the Judge’s summing up, the Judge held a discussion with Counsel about any clarifications required, without the jury present. (CT1464-1488)

At p.1486, the following interaction occurred in the absence of the jury:

MR ELLIS SC: The next point is, it was attributed to me that I said it was Mr Chappell’s blood in the dinghy. Now I don’t believe I did.

MR GUNSON SC: Yes, you did.

MR ELLIS SC: Okay – I don’t know why I’d say it

HIS HONOUR: Well –

MR ELLIS SC: Because I’ve never believed it.

HIS HONOUR: In opening.

MR ELLIS SC: Oh in opening –

MR GUNSON SC: Yes, in opening.

MR ELLIS SC: Oh okay, I abandon that, if I said it opening.

HIS HONOUR: All right. Well I’ll do nothing about that point. What’s the next point?

DO NOTHING?

In the summing up to the jury, immediately before they adjourned to make their decision, no clarification or correction was provided by the Judge on this point to jury members other than the following:

In other words luminol which reacts positively to blood but also gives false positive results did produce a positive reaction in area 11 [where the Vass DNA sample was taken], so maybe there was blood there, maybe the luminol was reacting to something else. (1529)

The Judge also made the following comment during the trial, in considering whether there was a case to answer, after hearing the evidence of the forensic scientist:

“There’s an abundance of evidence from which the jury could infer that Mr Chappell is dead, I don’t need to refer to all of that I don’t think, and that somebody killed him, there’s evidence of blood in the boat, sabotage of the boat, the positive luminol test on the dinghy, of the cut rope in photograph 42 particularly and of ropes rigged as if to have lifted something up to the deck. I think it’s open to the jury to infer that Mr Chappell was killed, hoisted out of the cabin, or out of the – hoisted up onto the deck, got into the dinghy and dumped in the Derwent, quite likely in a part of it that nobody searched. It’s – the – and it’s open to the jury to infer that whoever did that used the dinghy from the Four Winds that according to the accused had been tied up at the yacht club and was found abandoned at the beach near Marieville Esplanade.” (1084)

Sue Neill-Fraser did not have a fair trial. Her conviction is unsafe.

Geraldine Allan

August 25, 2014 at 18:01

Andrew Wilke, Independent MHR, statement yesterday (25/08/14)

“… Closer to home, there is a desperate need for Sue Neill-Fraser’s murder conviction to be reviewed. The revelation on 60 Minutes last night that Victoria Police forensic services has debunked the DNA evidence underpinning the guilty verdict surely must prompt Attorney-General Vanessa Goodwin to refer this matter back to the Court of Criminal Appeal. Unless certainty is brought to this matter the community will remain anxious about the effectiveness of our justice system.’’

For the purpose of emphasis in this TT thread discussion, the final sentence warrants reiteration, as it is a truism.

“Unless certainty is brought to this matter the community will remain anxious about the effectiveness of our justice system.’’

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 18:39

#27

Once again Eve Ash I call on you and your fellow supporters of Susan Neill-Fraser to release the entire trial transcript that you are cherry-picking quotes from.

Sections of quotes have been omitted several times by Ms Neill-Fraser’s supporters, to boost their own arguments. One of those actually occurred on this very thread.

So how do we know the same thing isn’t happening to the quotes coming from the trial transcript?

We don’t know, and we won’t know until the transcript is published so that we can all see it.

Steve

August 25, 2014 at 19:17

#23; Your point on the DNA is interesting. You contend that it is secondary contamination. 60 Minutes claimed that Victorian forensics had definitely established that it was a primary source.

Here we have two incompatible viewpoints on what is presumably a factual matter. Forensic science is a highly developed field and I find it hard to believe that they couldn’t determine definitely whether contamination was primary or secondary, especially in a situation where there doesn’t appear to be any deliberate attempt to mislead.

It appeared to me that the expert at the trial was coy because no importance had previously been attached to the question so he was only able to offer opinion.

With regard to the Luminol in the dinghy, I understand that an image of the dinghy, glowing with Luminol, was shown to the jury and they were told that this was a test for blood. If this is correct, many of the jury members may well have made their mind up there and then. Surely, you’re stretching things to say that the Luminol played no part in the conviction?

If there was no blood found in the dinghy, why not? We have a corpse, freshly beaten to death, being unceremoniously dumped into a dinghy, by a single person, in the dark and there’s not a single blood spot for forensics to find? The dinghy should play a big part in over turning this conviction!

Geraldine Allan

August 25, 2014 at 19:31

#30, FYI Steve, in case you have missed it, Barbara Etter APM 24 August 2014 blog post, headed: An Analysis of the Supreme Court Trial, the Court of Criminal Appeal Submissions and Decision and the High Court Application in relation to the Meaghan Vass DNA Sample

Barbara writes,

Please see attached an analysis of the Court transcripts and decisions relevant to the consideration of the new and startling DNA evidence in the Sue Neill-Fraser case in light of the new expert report from Victoria which indicates that the relevant sample was directly transferred to the deck of the yacht, contrary to theories put by the Crown to each of the courts. See Analysis of Court transcripts etc.

http://www.betterconsult.com.au/blog/an-analysis-of-the-supreme-court-trial-the-court-of-criminal-appeal-submissions-and-decision-and-the-high-court-application-in-relation-to-the-meaghan-vass-dna-sample/

Eve Ash

August 25, 2014 at 19:35

#30. We should advise the National Museum in Canberra to reserve a spot for the Four Winds Dinghy to sit alongside the Chamberlian car.

It was Sydney forensic biologist Joy Kuhl who claimed there was baby’s blood in that car and on family possessions. Years later Justice Morling found that a reasonably instructed jury in possession of further evidence would have been compelled to acquit. The royal commission revealed there was no blood in the car, or on the Chamberlains’ possessions.

Geraldine Allan

August 25, 2014 at 19:40

#29 Ben, that I am aware, there is no available online facility that provides court trial transcripts. I can only imagine that the volume of the Supreme Court SNF trial transcripts is huge. Thus, can you please say how you believe it is realistically possible “…to release the entire trial transcript that you are cherry-picking quotes from”?

From my viewpoint, you are asking the impossible, other than you attending the Supreme Court to peruse the records, if that is possible.

Rachel L

August 25, 2014 at 19:51

Thanks to Ben for taking on those questioning the verdict. I followed the case closely and read all the documents associated with it at the time. I believe, as the jury does, that Neill-Fraser is guilty. There is such a classic lot of spin being done by her supporters. Associations with Lindy Chamberlain are ludicrous. Lindy never lied or changed her story. There was no media pack out to discredit Neill-Fraser, as was the case with Chamberlain case. 60 Minutes is tabloid journalism. As an earlier posting said; almost as good as Frontline!

They should release the full transcript and stop cherry-picking to suit their point of view.

Geraldine Allan

August 25, 2014 at 20:43

#34, Rachel, since you “read all the documents associated with it at the time” you might provide your source of reading to Ben, in order that he can read for himself a full non-cherry-picked version.

For this record, never have I met the now convicted SNF. I readily admit I do not know if she is innocent or guilty, how could I? What I do know is — she was and remains entitled to a fair trial. Shamefully, that didn’t happen. If my supporting calls for a fair hearing to come about, then I come into your category of “supporters”.

As one of those “supporters” I (and other commentators as I read them) do not engage in “spin to suit [my] point of view”. Staying with the facts is much safer and adds credence to matters at issue.

Anyone has a right to hold an opinion and courteously express it as is happening in these discussions. Graciously, I ask that the respect be reciprocated.

Garry Stannus

August 25, 2014 at 21:38

In the TT article ‘It’s time to talk about Sue’ ([Here]), Geraldine Allan (#4 in that thread) quoted from Justice Byrne’s (Baden-Clay case) repeated summary comments to the jury – repeated at the jury’s request. He said:

I would have no difficulty in inferring from ‘new’ Victorian forensic evidence that a person other than SNF was actually on the boat around the time of Bob Chappell’s disappearance. Knowledge of this might well have prevented me, had I been a juror in the trial of SNF, from concluding that she was guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

The subsequent refusal by the trial judge to require that other person to be recalled to the stand, following the discovery that she was not where she’d claimed to have been on the night of the disappearance, was – in hindsight – a mistake, or, if you like, a miscarriage of justice.

Ben Lohberger makes a good suggestion in calling for the trial transcript to be released. In my opinion, this would be in the public interest. However, Ben (#13), in writing about the expert evidence that “the homeless girl’s DNA could have been transferred onto the yacht by foot traffic, or by any other meansâ€, seems to be confusing matters. It seems as if he is responding to the new report from the Victorian Police Forensic Department, but yet it seems as if he is not. Is he simply reiterating what is part of the existing court record? Be that as it may, I call on Barbara Etter / Eve Ash / or similar persons who have copies of relevant transcripts, to put them on the public record, here on Tasmanian Times, where we can all look at them as complete documents. If they are too large, then I suggest they be broken into files within sub folders etc.

I also call on Barbara Etter / Eve Ash / or similar persons to release the entirety of the Victorian Police forensics report. At the moment all that I have access to is the following excerpt:

– published by BEtter Consulting: [Here].

I am concerned that the ‘there-is-no-evidence-to-support-the-secondary-transfer-of-DNA-hypothesis’ statement is being used to claim some sort of de facto proof that the DNA was deposited directly.

I would be more than happy if Barbara/Eve were to publish the whole of the police report and to find that the Victorian Police report insists that the DNA was deposited directly. However, I fear that this is not the case, and I fear that in fact the report might actually say something less supportive of the SNF claims. Perhaps the whole report is somewhere readily available, and perhaps I’m the only person who cannot locate it. But while I can’t read it, I wonder about that quote, which I gave above. Its ‘[T]here is no evidence’, beginning as it does, with a capital substituted in place of a lower case ‘t’, suggests that there was originally more to this sentence than was published by Barbara. There are a number of reasons why we do not quote entire sentences. Some excisions are sensible, while some are to present an idea in the strongest possible light. Sometimes, people leave out that which contradicts their own view in order that theirs might prevail. I am concerned that the report might not contain all that Barbara and Eve claim of it.

Here is the above quote, again:

I recall and modify a legal maxim thus: absence of evidence of secondary DNA transfer is not in itself evidence of direct deposit

Steve

August 25, 2014 at 21:49

#34; My problem Rachel, is that I don’t believe that “belief” is sufficient reason to lock someone up for twenty plus years

I have always kept an open mind on whether SNF is guilty or not. There’s some facts that don’t look good for her, but to my mind, none of them constitute proof beyond reasonable doubt. The judge appears though to agree with you, as somewhere in that summing up (sorry, I haven’t time to extract it so I may be misquoting)he instructs the jury that if they don’t believe the prosecutions sequence of events, it doesn’t really matter as the important thing is that they are satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that SNF is guilty. Basically, if you believe she did it, regardless of the flimsy evidence presented…..

Interestingly, as I have looked harder at the “farrago of lies” that appears to be the backbone of the “she did it, I know it” faith, I see not the lies I expected to see but a confused person, upset and not taking a lot of interest in what she is saying because she doesn’t think it important.

Ben has listed what he feels are the overwhelming facts proving guilt. I just see a collection of stuff, that when piled together looks impressive, but when looked at in context seems ridiculous.

Twelve years ago SNF discussed killing someone. Really? This mild mannered lady has spent the last twelve years plotting a murder, discussing it with nobody since and then she pulls off this ham fisted effort? Even Miss Marple would choke on her digestive!

Ben Lohberger

August 25, 2014 at 23:01

#33 Geraldine

Eve Ash, Barbara Etter and Andrew Urban all appear to have access to the trial transcript, and all of them are cherry-picking quotes from that transcript.

I don’t know if you actually read Andrew Urban’s article above, but he quotes from the trial transcript and names up the page numbers (“In his closing (CT pp.1428 – 1461)”).

Eve Ash also appears to be quoting from the trial transcript in comment #27.

Without wanting to be rude, you should probably read what is written on a thread that you’re commenting on. It’ll help you to stay with the facts, and would add some credence to what you’re saying.

As for #35, that first sentence is far ruder than anything said by Rachel.

Garry #36, I included the expert quote from the trial, about the DNA possibly coming from foot traffic or from any other source, because the only quote I’ve seen from the new DNA report specifically refers to a lack of evidence that it came from “foot traffic”.

Ms Neill-Fraser’s supporters say this finding debunks the DNA evidence given at the trial, but the trial evidence specifically mentioned that it could have come from pretty much anywhere.

Which means this new analysis of the DNA is basically irrelevant.

Rosemary

August 25, 2014 at 23:28

Tas Times is not a replacement for proper judicial process, there is enough published trial material to warrant a review of the case and quashing the conviction while still respecting legal in confidence. same with reports. all should rightly go before the courts through a proper review process where new evidence can be dealt with. I recall the challenge from a police officer speaking on behalf of the police association on the news calling to produce new evidence. now the challenge can be reversed, with this new evidence can the A-G open a judicial review with proper legal proceedures. Inquiry Now! The police should welcome scrutiny for the public to have confidence in them. As should the whole legal system in Tasmania.

Rachel

August 25, 2014 at 23:49

A jury and our legal system found her guilty beyond reasonable doubt. What Neill-Fraser’s supporters are trying to do is have a trial by public opinion, in order to push politicians to their cause because they have had no success with legal avenues.

In that case they should make freely available all the transcripts so others can read them and make up their mind. If they are of the business of trying to convince others of her innocence and having rallies and a campaign to free her, then they should have nothing to fear putting that information out there to show just what a horrible miscarriage of justice this is all meant to have been. Far better to do this than the current situation where they discredit themselves, by trying to convince others with selective quotes, a documentary is made, again with selective information and tabloid journalism, by way of 60 Minutes, is brought to the cause.

Better still the courts should re-release the entire transcripts so the public can read it all for themselves. It would definitely be in the public interest.

Steve

August 26, 2014 at 00:15

# 36; Thank you Garry for a sensible comment!

My personal opinion is that, in this situation, where there are so many vague theories floating about, so much lack of solid facts, it’s preposterous to not simply re-visit the trial.

I don’t care what rules apply to appeals. For ongoing faith in our judicial system, there needs to be the facility to say whoa; there may be a problem here. Let’s go back to square one and start again.

Take the egos out of it, simply start again. I get a bit concerned when I read the offerings from the “she’s guilty” faith. This is a real person, locked up for the next twenty years? If I thought her guilty, I would remain mute.

dna sceptic

August 26, 2014 at 01:00

The science of DNA has made huge leaps over the past decade. But the science of its transferral is in its infancy.

Once thought to constitute a lay down misere, DNA evidence is now viewed with scepticism. Check the case of the Faceless Lady at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phantom_of_Heilbronn.

There was also a SA case which ABC RN’s ace legal reporter Damien Carrick ran recently http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lawreport/jeremy-gans/5677452.

And to add further doubt read ‘The Tainted Trial of Farah Jama’ by Julie Szego which describes how a Melbourne kid of Somalian origins was recently fitted up for a rape.

Geraldine Allan

August 26, 2014 at 01:04

#38. FYI Ben, I twice read the complete article, and have read all comments.

I consider there’s nothing wrong with my comprehension. Be that as it may, I accept that as you interpret my comments, my appreciation of the facts may need a change for the better.

Having addressed the digression, it is now time to get back to the real issue — campaigning for a fair trial [justice] for Susan Neill-Fraser and for dignity to be afforded to the memory of Bob Chappell. Then and only then, can his family and loved ones deal with his loss and grieve in privacy and peace.

Steve

August 26, 2014 at 01:48

#42; Fair comment dna sceptic, but are you suggesting this happened in this case? I’m happy to accept that science is not infallible but there doesn’t appear to have been any scientific investigation of this point that went beyond one expert witness being asked questions that I suspect he was not in a position to answer categorically.

Ben Lohberger

August 26, 2014 at 03:00

#43

Geraldine, I suspect Bob Chappell’s family are already dealing with his loss, despite the fact that his body is still missing.

They do not need to see his murderer released to achieve peace. In fact quite the opposite.

Your comment also implies that if Susan Neill-Fraser is not set free, her supporters will continue their campaign regardless of any distress it may cause the Chappell family. And you’ve said something very similar before, on another thread:

“…for the record I am concerned about the victim and endeavour to take into consideration the sensitivities for all persons involved in and affected by, the tragic set of circumstances of this matter.

Additionally, it is important for citizens to have faith in the criminal justice system. Until such time as justice is seen to be done (not said to be done), it seems to me an impossible task to put associated matters to rest and afford all the dignity and respect they so deserve.

It seems to me that until such time as those with the power to shine light on matters as exposed, discussed and debated, associated distress for all parties will continue.”

Posted by Geraldine Allan on 11/08/14 at 01:10 PM

[ http://oldtt.pixelkey.biz/index.php?/article/oa-objections-answers-why-should-dr-bob-moles-be-heard-by-mps/ ]

If the Neill-Fraser supporters *really* cared about the Chappell family, or about “affording dignity to the memory of Bob Chappell,” they would be talking to Susan Neill-Fraser about admitting her crime and revealing what she did with Mr Chappell’s body.

And if they actually cared about Ms Neill-Fraser, they would be encouraging her to do exactly the same thing.

She will never receive parole while surrounded by people who are actively encouraging her state of denial.