Playwright Joanna Murray-Smith gave the keynote address at Playwriting Australia’s National Play Festival in Adelaide last night where she talked of the personal and the political, her interpretation of the “political play”, of our political leaders in light of the Federal Arts Minister stripping $105 million from the Australia Council, and the indifference to the arts by our political leaders. In light of recent events she asked ‘What is the role of artists?’”

“To stand apart from authority, to be sceptical of power, to engage with human struggles and articulate them for others, to be free of cant, to embrace mystery, to be self-revelatory as a means of articulating the human experience and the determination to say what needs to be said,” she answered at the Adelaide Festival Centre tonight. The full speech is published below.

A Lover’s War – Joanna Murray-Smith

I have been a professional and prolific, sometimes successful, sometimes unsuccessful writer for almost thirty years. I’ve been well reviewed, badly reviewed, had good years and bad years, have vowed to end it all many times, but as I have often said, a writer needs only to have an ego that just narrowly outranks their vulnerability. Like most writers, I learnt the hard way the truth of Kurt Vonnegut’s wonderful description of the writing life: “We have to continually be jumping off cliffs and developing our wings on the way down.”

Despite nearing the precipice of desperation many times, I’ve not only kept at it, but I’ve felt there isn’t enough time to write all I want to write. There is a perpetual calendar that hovers above me, and with each strike through each day I write (or think) a little bit faster.

Around the time I had my first baby, I found a way to turn every form of engagement with the external world around: to shift all senses back through the wardrobe door into my own private Narnia. This has made me, perhaps, a sometimes inadequate mother, but I tried to make up for it by having no specific timetable. I don’t work set hours. I am a mother when I most need or want to be and then, using a form of invisible immersion, I open the wardrobe door. I’ve trained myself to write in a supermarket queue, in a school playground, at the football, in an airport. I can even write a new play when doing a live radio interview about an old play.

In May 2013, my mother died. My mother – a Polish Jewish refugee who spoke five languages, spent her youth in the Communist Party, taught and lived in London and Prague, became an exceptional English and History teacher, an Anglophile, unofficially co-edited my father’s literary magazine Overland and a cover to cover reader of the New Yorker until two weeks before her death at 87, a legendary hostess to the writers and artists of a generation – well, let’s say she knew a lot about a lot of things instead of (like me) a little bit about not very many.

My mother has always championed my work and demonstrated at times embarrassingly vocal pride in all three of her children, but her role in her children’s lives was also as a potent critic. She was my P.R. champion and my personal Ben Brantley rolled into one. What made her an exceptional person made her, sometimes, an infuriating mother. She believed she knew best and mostly, she did. Like most mothers, her silence was often more expressive of her criticism than her words.

The tough part of me – that icy part that Graham Greene referred to as an essential aspect of the artist’s make up – figured that her death would in the profoundest way free me as I no longer needed to worry – even unconsciously – of what she would think.

Her death capsized me. I tried to camouflage my grief. I used travel and work to hide in, to filter and tidy up the emotions I could not handle in life. In 12 months, I went to Bali, Tokyo, LA, New York, Mexico City, Havana, Paris, Berlin, London and Amsterdam – some of them twice. I loved airports. Some of it was work but mostly it was simply trying to drown out the ticking clock of my life, a sound that had grown with sinister intensity, since my mother’s death.

There was something satisfyingly symmetrical in being orphaned and physically stateless. Motherless, I felt entirely new, so the old patterns of behaviour seemed wrong. Who knew that the affected independence I had always expressed by rebelling or arguing with my mother was its own form of dependence? Now real independence was manifesting itself as a kind of existential aloneness. Instead of feeling the cool wind in my hair in Paris, I was lying in bed in a Havana hotel room wondering what I was without her. And the dawning sensation snuck over me: despite the fact that I had never felt mortality shadow me more diligently, I didn’t want to write as much as I had. Some ever-burning pilot light, that for most of my life took only a free half hour to ignite into a burning flame, had gone out.

I saw the world’s greatest psychiatrist. I said to him: I think my mother was my pilot light. I don’t need to impress myself as much as I needed to impress her. I feel as if my life is over. I feel as if I’m going to die imminently. I don’t see the point of writing because nothing I write is good enough.

You’re a very successful writer, he said.

What is the point in being a not good enough writer? If one can’t be the best writer, why be a writer? Why be just another writer? If I have nothing really valuable to leave behind when I die – what is the point of continuing to write?

And the psychiatrist looked at me for a moment as if – it seemed to me – he needed a moment to absorb the peculiarity of my perspective. “What if the work is just about now?”

“Now?” I repeated, confused.

“Maybe it’s just about what happens here.”

His words came barrelling towards me like a giant piece of rock down a mountainside, imminently about to crush every rational assumption of purpose and value I had ever had.

I’m the daughter of an historian and a history teacher. My father kept bra receipts of my mother’s from 1957. When going through my parents’ belongings recently with my siblings, I found parcel after parcel wrapped in brown paper and string and inside was every squiggle, every finger painting, every school exercise book and project I had ever done, many of them annotated in his hand “ A horse eating a carrot” or “Jo became very angry when she had to explain this is a picture of space”.

I’m not my father but some lessons are hard to unlearn: value to me has never belonged to the present. The past has already past the test of significance, since what if we recall it, it has endured. The future is the place that bestows significance on the past, a retrospective Honour board. I have spent my life trying to predict it, in work, in love, with purchases, with children. I am consumed by the hypothetical. As long as I can remember, I’ve tried to get a jump-start on the future. But the present? The present has always had the lowest ranking of all for me. Dressed in the minutiae of ordinary pursuits, the ephemera of the domestic life, the admin of life, and mourning for what is over it’s a funeral parlour for the past and a half-way house to the future.

But at this moment– the thought hit me like a truck – what if everything – everything really important is happening now? My daughter’s expression this morning when she saw me, the spontaneous chat with the DHL guy, the walk in the sun with the dog, the one good paragraph.

Embarrassingly, more than any pleas from charities, any political call to arms – this thought has made me conscious of the power of words as an arsenal. David Hare said: The act of writing is the act of discovering what you believe”. Well, it’s a bit belated, but what do I believe? Do I know what I believe? All these years we think that we place our values and philosophies into our work, that we make them containers of our beliefs but perhaps it’s the other way around. Is it, in fact, the plays which tell me what I believe and what I believe in?

So often, what I believe is the play I’ve written and what I come to understand of the play I’ve written are two entirely different things. All the conscious intentions have been suffocated by the unconscious ones. I may be consciously improving structure, embedding ideas in my stories and characters but the blood of the play is in the cracks between the conscious choices, veins of intimate, bewildering curiosity that lead me places I don’t really want to go.

Last year at the National Play Festival, Andrew Bovell poetically and passionately talked about national shame and pride and the intersection of history and the present, a stirring, captivating exploration of a writer’s grappling with what is important – a speech that made many of us think more deeply about our country and ourselves.

I listened to it whilst still inside the most profound grief and fragility. Although, as I said to Andrew, there were things I disagreed with, the passion with which he spoke connected with the kind of life and death perspective of my own mental state. Who am I without my mother seemed to segue fluidly into some of the touchstones of Andrew’s speech.

What is the responsibility of the artist to his or her society?

Every time I have had an emotional encounter with an audience member, the incident stays luminously present. There is the 93 year old man who’d never seen a play before and came to the opening night of Ninety in Geelong and cried because the play articulated his feelings on the death of his baby seventy years before. The sobbing women who hugged me outside the Belasco Theatre in New York, because Honour articulated their sorrow and rage at being left by their husbands. Most surprising of all, the man sitting in front of me at Pennsylvania Avenue who asked me if I was the writer and then shook his head with astonishment, choked up with emotion (which I choose to interpret favourably!).

Part of me wanted to grab them all and shake them and remind them that the world they just watched started as a flicker of a thought inside the liar that is every writer. It’s all phony, I want to yell! I was manipulating you! Those people up there only seemed real because real people spoke for them, but don’t confuse the actor with the script. They’re getting paid to trick you – not much, admittedly – but still. Wake up and smell the coffee!

But the believer inside us who grapples and fights and usually (though not always) wins against the cynic inside us, knows that these audience members have crossed the border of the individual into the country of shared experience. They have put aside their existential aloneness, which includes worrying about where they parked the car or their work-place bullying counselling session or reflecting on the price of theatre tickets, into a voluntary collaboration.

They have allowed themselves to give us, the storytellers, the one gift we long for – the suspension of their disbelief. And in the best moments for them and for us: they are bringing to our fiction their own feelings and experience and history, and in so doing, they make a fabrication pulse with truth.

We don’t stop very often to ask what it was that allowed them in because we like to think it inevitable – the end product of our talent. But if we stopped to wonder, or ask, it might be a line that triggered a memory. A character who reminded them of themselves, perhaps? A humour that connected? A hypocrisy revealed that made them feel instantly less alone? An idea they’d had but never articulated? The face of an actress who reminded them of their mother or daughter or lover, seducing them into our story? Or just skilful suspense, mastered over years of what has been – in Australia – largely a self-taught trade.

Somehow those audiences give up their vigilance about their reality: sitting in a seat in a theatre, they gave up their scepticism, cynicism, logic, emotional defences, their privacy to join with us in our fantasy, to find in our personal revelations some revelations about themselves.

When a playwright sits amongst an audience and shifts their eyes sideways to take in an expression of submission, when a playwright hears the laughter or feels the transition of reality from auditorium to stage, a transition that happens in a mutual seduction of artists and audiences – that is the moment when a playwright succumbs to the love-affair of a writing life – a love affair with that amorphous, sometimes frustrating, occasionally disappointing and often inspiring lover: the audience.

We don’t talk about our lover very often. We think of ourselves as more interesting. The audience encourages this by fanning the flames of our self-importance. And in the full swing of our egocentric flourishes, we sometimes forget them – but we do so at our peril. Everything we are, everything we want, everything we need and everything we aspire to is in their hands.

In those moments comes a question. It’s a question that I do not consider in the room in which I write. It’s a question I divert from in playing with dialogue, a question I camouflage in the set design of my imagination, the question I refuse to respond to when it first whispers to me in the rehearsal room… What is my responsibility?

All those years in apprenticeship seemed consumed with the responsibility to honour my own intentions. Isn’t the artist’s only duty to answer their deepest instincts – to bypass choice, to absolve themselves of responsibility? Is the responsibility of the artist to their muse –about marshalling a determination and stoicism in the face of failure or injustice or poverty. Maybe an artist’s responsibility is simply to resilience?

As a young writer (before age made me more human) — I felt responsibilities not to bore, not to indulge myself, not to pander to fashionability – not all of which I met.

But once the worst peaks of youthful narcissism are reached and the downhill descent begins, the question grows louder: what is my greater responsibility to the world I write for? Is there one? What is the responsibility of all artists to their world? Or is responsibility irrelevant to creativity? Greater minds than mine have wrestled with such questions.

I say this because for almost as long as I’ve been writing, and perhaps in deference to a childhood dominated by left-wing politics, I have steered away from the self-described political play. By the time I was born in the 1960s, my parents had left the Communist Party, the headquarters of both their youth and their passion. When Russia invaded Hungary in 1956, the dream was over and as the certainty and simplicity of a deeply ideological commitment began to fade, a vigorous scepticism of any hard-line ideology – from feminism to environmentalism and every other ism – became their new faith.

I grew up in an environment that put intellectual freedom above any kind of political fundamentalism. My parents saw the dedication to a political ideal – any ideal – as necessarily a betrayal of the subtleties of the human condition. That faith became enmeshed with my own creative personality.

I don’t believe much in the play that struts the most literal sense of politics, that feeds from or delivers polemic – although admittedly, if I lived in China or Afghanistan or North Korea, I might feel differently. It’s not just that I distrust it or that I feel cheated when knowing a writer’s intent – although both of those are true, but because they bore me. Such plays always feel as if they are preaching to the converted and artists must – as the art critic Terry Teachout once wrote – “have freedom from the paralysing obligation to persuade”.

I often read that there is a longing for plays about something, as if that can only be constituted by ideological vigour. But for me plays about something are usually about nothing. The message flattens out anything unpredictable and over-clarifies anything opaque. I’m bored by my own capacity to see “the point”. I want the play to be smarter than me.

By contrast, plays about nothing – three sisters, perhaps, who want to go to Moscow but never get there or a bored housewife who shoots herself – have always been the cornerstones of political insight. For decades my plays were seen by the major critics – an oxymoron if ever there was one – as bourgeois dramas or comedies about middle class characters worrying about first world problems. As a young writer I was baffled by this. The plays may be accomplished or hugely flawed – but my intention was always a radical one, albeit packaged strategically inside a comfortable and unthreatening landscape. What better place to play out cut-throat ideas of morality than a world full of the comforting accoutrements of success – a world the audience (in the main) belongs to?

A man who forsakes love and history for passion, a wife who has given up her creativity to encourage the professional charisma of her husband, a feminist who adopts out her daughter and forsakes her personal responsibility to a little girl while espousing a public responsibility to feminism, a successful and brilliant medico who took part in a terrorist event in her youth – can a lifetime of penance undo youthful misdeeds?… These are the plotlines of my plays and in every case they succeed where and when those themes are rendered invisible by layers of convincing humanity and an authorial uncertainty. I know without fail that if I know too surely what I think, the play will fail. Its edge, its danger, its threat, its interest… its politics – these are present in the questions of the play and not in the answers.

When I wrote The Gift – a play about a couple who want to give their four year old away because they feel their fidelity to their creativity is more compelling than parenting – there wasn’t a critic in the country who engaged with the monstrousness of that theme. To them, it was a play about two couples bantering in a holiday resort – another Joanna Murray-Smith play about people with Bang and Olufsens talky-talking. The setting of my plays – in the familiar halls of the middle-class — has always taken precedence in the critical mind over sometimes quietly revolutionary questions. Not that they’re well handled or successful – but for better or worse, they are the foundations of the intent.

In a pitch to a theatre company would this play get the commission?:

“It’s a comedy, there are three women’s parts, six men’s, four acts, landscapes (view over a lake); a great deal of conversation about literature, little action, tons of love.”

(That’s Chekhov describing The Seagull).

We have a responsibility to have courage – the courage not to hide our fundamental privacy in layers of literary gift-wrap, but to expose ourselves, reveal ourselves, state the inconsistent algebra of our lives where nothing properly adds up, no characterization runs true to type, where all structures and systems incorporate their own saboteurs.

“If it sounds like writing, rewrite it”, said that genius writer, Elmore Leonard. The best writing is the writing that channels up from the dark, that bypasses the intellect, that defeats our less interesting strategies. Our hearts are more interesting than our heads – at least at the beginning of invention. We need to get out of the way of those inner vibrations which tell us what we care about, what hurts us, what matters. They are the arteries that feed the soul, not the bland school Marms of our conscious minds, trying to corral ideas into tidy lines.

This complicated and often unlikeable aspect of our personalities is the stuff of great and compelling writing. What doesn’t make sense to us, most likely, is what will make the play true. Our faults, our vulnerabilities, our mystery to ourselves all make the words hit the target of the deepest humanity. The mystery is what we owe ourselves and our audiences, since anything less is short-change.

But courage comes in many forms. It comes in self-exposure. It comes in facing our own weaknesses, in calling ourselves on fraudulence. Courage comes in simply writing in the face of all oppositions: time, doubt, criticism, poverty and in making allies of those things that could scupper our creative plans: paying jobs, desperation, children.

And outside of the writing itself, courage comes also in saying what is important out loud, at the cost of something. Because whatever the cost is, the cost of silence is a greater cost. And if we don’t have courage, we don’t have anything except pragmatism and pragmatism is not and never has been art.

As Tom Stoppard said: “Responsibilities gravitate to the person who can shoulder them.” Well, we can shoulder them because a fearful writer is not a writer worth being.

Yes, I grew up in an atmosphere of suspicion around ideological fervor but I was also the daughter of “doers” – a father whose distaste for hardline ideologies was matched with an equally vigorous sense of possibility. Their belief in writers and writing was also a belief in creative thinking, in imaginative evolution, in change. They were the opposite of cynical and in my father’s ardent adoption of personally appealing causes – he was President of the Australian Lighthouse Association, as well as the Anti Metric Association and he managed to get the streetlights obscuring the view of the bay on Oliver’s Hill in Frankston moved to the central median strip – this belief in the power to change and that from little things, big things grow was a powerful bequest.

It’s a bequest I have not lived up to. And perhaps when my mother was alive, I let her be the shining light of conscience, as my father was. But perhaps I can start with the smallest act of good intentions which is to say out loud what I think, a practice that Australians often seem to consider pretentious or self-important. (We have to get over that).

What I say here, I hasten to add, is not as a spokesman for any organisation. I speak entirely as an individual and playwright.

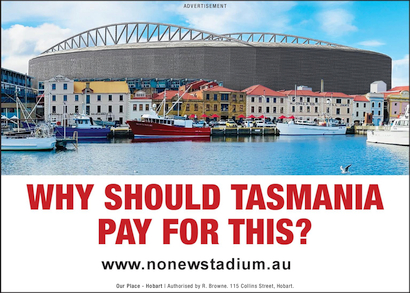

Recently, over the issue of the withdrawal of funds from the Australia Council and the establishment of the Minister’s own enterprise, the NPEA, we have seen frantic, hair pulling board meetings, hysterical public statements, provocative defences, demonstrations, letters to editors, Senate enquiries and a bonfire of opinion in the blogosphere. Artists, artistic directors and arts administrators have been rendered voiceless. Rumours abound that the silence of the main-stage companies has been quietly required by the powers that be, threats implied. Those vocal champions of art, those eloquent arts leaders, including those who have always prided themselves on their iconoclasm, are silent in their offices, biting their nails.

That this is happening seems all a bit too Gotham City to be believable. Surely, the Arts Minister – by repute an intelligent and cultivated man – is not seeking to brand artists as foes, or to divide them into the good and the bad.

I have faith that the Minister is smart enough and confident enough to listen to arguments and commentaries, sift through them for unexpected truths or lessons, and hold his ground or shift his own position accordingly. Surely a politician – any politician but particularly one with an appreciation of the artists, the one profession where fearlessness and independence is actually a prerequisite – would not actively encourage sycophancy? What sort of culture would we have if artist’s pragmatism won over their conviction?

What purpose are artistic organisations if, when faced with pragmatism versus idealism, they give in to intimidation? What is their role if not to stand up for the artists and audiences of their constituencies, to fight for the freedom of the imagination which sometimes leads to good work or bad work, popular or unpopular work, extended seasons or box office failures — but which in all cases forcefully exercises the muscle of observation over humanity and our world?

Well may we ask of the major companies and arts institutions who have not said a word, or much of a word, including companies very dear to my heart. Well may we ask of Craig Hassall the CEO of Opera Australia, whose response to the potential decimation of many organisations who train, employ, educate and encourage the kinds of arts practitioners that Australia wants and needs, was as follows: “Speaking [for] Opera Australia, my first thought is that I am relieved and delighted that major performing arts companies’ funding hasn’t been cut … I don’t really have a view on where the money comes from, as long as the government is spending money on the arts”.

Craig Hassall’s first thought is not a sense of concern for the survival of smaller companies less able to fend for themselves, who in many cases do an exceptional job on shoestring budgets, who educate, train, encourage and foster the kinds of artists who eventually elevate the reputation of Opera Australia in their excellent work for that company. I love Opera Australia, I’ve being going to it all my life. My new opera, commissioned by Opera Australia, is being filmed literally as I stand here. I’ve met Mr Hassall at Opera events and he seems like a nice man. But his appalling statement is more than unwise – it’s uncouth.

Leaving aside how our politicians want to spend the arts budget and on whom, who they want to prioritise over whom, is not really my point. Politics are what they are. But for writers and artists, living dangerously (emotionally, financially, intellectually) is rocket fuel — are we really too scared to speak? Do we have a system where a single politician in one of the healthiest democracies on earth can make the loudest, most audacious and maverick and truth-seeking, most alert and vital, most liberated voices in society tremble? The answer has been until now — apparently, yes although some of those Senate submissions I know will make up for lost time.

All the arts organisations, big and small, high and low, left and right, traditional and radical need to join together and make a point that rises above self-interest and the party political. They might have summoned a powerful cri de coeur that would have promoted hope in the smaller companies, made themselves look like leaders and reached the public with more direct, impassioned sense of what was at risk. They might have made a collective plea: The arts are sacred, they make life better, they make a country stronger, they make a people think more deeply, they make us laugh, they communicate our sorrow, they heal us – let us tread carefully?

Where is our courage? Matisse advised Brassai, “You have to be stronger than your gifts to protect them”.

In 2013, Australia Council research found that 15 years ago “one in three Australians thought arts were ‘not really for people like me’. Today it’s only one in nine”. Thirty per cent, agree with the statement that “The arts tend to attract people who are somewhat elitist or pretentious”. This whole wondrous world from Henry Lawson to Declan Greene, from Katherine Susannah Pritchard or Dorothy Hewett to Meow Meow, from John Glover to Ben Quilty – this whole wondrous world they feel distant from, suspicious of or excluded by. Why?

It might be because though we may see our politicians at the Australian Open finals or the MCG, they are rarely seen in theatre foyers or galleries – although Tony Burke and George Brandis are exceptions, as were John Cain, Bob Carr and Paul Keating in the past. Politicians are rarely – is ever — heard speaking about the importance of the artist to this country.

They are rarely heard uttering an artist’s name, unless it is to call them “disgusting”. Chasing some imagined philistine vote-catchment, they decry the controversial or ridicule the extreme. Kevin Rudd demonstrated very aptly that he was prepared to sacrifice integrity for votes in decrying Bill Henson. No one will ever know if Bill Henson is a great artist, an exploitative one, whether his art is beautiful, corrupt, successful, a travesty. It is what each one of us makes of it.

It is not a politician’s job to judge us, influence us, punish us – it is their job to convey to their constituency, the nation, that in the imaginations of Australia’s artists is an essential beauty that improves, entertains, stimulates, comforts and elevates us and our experience.

But our politicians do not show by example. They do not lead by example. They do not inspire. Paul Keating was the last Prime Minister to show any interest in the arts and none have filled Whitlam’s shoes with regards to elevating the arts to an essential component of national identity.

David Williamson has recalled that in 1971 when Whitlam was opposition leader, he went to the opening of David’s play Don’s Party, which you may remember is set during a suburban party on the night of the 1969 election, when the anticipated Labor victory is thwarted. Whitlam telegrammed Williamson the next day telling him he would need to change the ending as Labor would win the 1972 election — and he was right.

The chance of a contemporary Labor politician calling a playwright the night after an opening is not something I’d bet on. It’s hard to imagine a politician of any persuasion naturally expressing gratitude for an artistic experience.

I make the following point only because it’s a point that needs to be made – I’ve had eleven play seasons at just the MTC and the STC, had numerous productions at the (Sydney) Opera House and am regularly produced around the world. I’ve written hundreds of roles for Australian actors, created work for hundreds of builders, technicians, stage managers, directors and designers. When I met the current federal Minister for the Arts last year, he looked at me quizzically and responded to our introduction with: “Oh yes, I think I’ve heard of you”.

JFK said: “If art is to nourish the roots of our culture, society must set the artist free to follow his vision wherever it takes him.” The White House, under Kennedy, pulsated with American artists and the Kennedy’s elevation of the arts into the national consciousness cemented its role in what it meant to be American.

In 2007, Jacques Chirac spoke of the French government’s intention:

“…To hold up the infinite diversity of peoples and arts against the bland, looming grip of uniformity. To offer imagination, inspiration and dreaming against the temptation of disenchantment. To show the interactions and collaboration between cultures…,which never cease to intertwine the threads of the human adventure. To promote the importance of breaking down barriers, of openness and mutual understanding against the clash of identities and the mentality of closure and segregation. To gather all people who, throughout the world, strive to promote dialogue between cultures and civilisations. France has made that ambition its own. France expresses it tirelessly in international forums and takes it to the heart of the world’s major debates. France bears it with passion and conviction, because it accords with our calling as a nation that has long prized the universal but that, over the course of a tumultuous history, has learned the value of otherness.”

Can we imagine an Australian politician making such a declaration? Can we imagine Tony Abbott or Julia Gillard quoting a line from Voss or inviting Chris Wallace- Crabbe or Andrew Bovell to The Lodge? Did Kevin Rudd say: “There is a deep affection in Australia for the Arts. And I mean the arts have been important to me ever since I was born. I mean the arts are part of the firmament of Australia’s sort of national life; there’s a deep respect for their role.”

No, he said:”There is a deep affection in Australia for the Queen. And I mean the Queen’s been the Queen ever since I was born. I mean she is part of the firmament of Australia’s sort of national life; there’s a deep respect for her role.”

The battle we have is to seduce Australians into the possibilities that lie before them, whether that is Jennifer Kent’s Babadook, Marion Pott’s Lear, Elena Kats Chernin’s opera, Eddie Perfect’s poetic epiphany about Mentone, Chunky Move’s “I want to dance better at parties”, Simon Stone’s Wild Duck or Keating, The Musical.

Artists are not the enemy and must not be made the enemy. This is no time for a culture war between Left and Right, rabble rousers or traditionalists.The war we all need to be fighting is that in defeat of dreariness, of the euphoric against the pedestrian, of the imagination against philistinism, of knowledge against ignorance, exhilaration against boredom, of illumination against weasel-words, of big thinking against petty. The war isn’t really amongst us – governments, ministries, politicians, arts companies big and small – it’s between believers and non-believers. The battle we should be fighting is against the ignorance of those unconverted to the disparate, mysterious, contradictory, engaging voices of Australian artists who seek, one way or another, to make a contribution to make life more interesting.

Bring the people to the work, lure them, seduce them, woo them — or bring the artists to the people, but let us see our artists – in their successes and their failures – as being on a worthy road – a road they are on for no better reason than that it feels like the only road – and whose motivation is to illuminate what it is to be alive.

Put our artists on the front pages, celebrate their triumphs, put their works on our streets, let’s see them on Q and A – an Australian poem read every Monday at school assembly – Great Australian novels and plays taught in our academies, a National Day for Art as well as for a horse-race or a royal birthday – let’s see a Australian artists sprinkled heavily through the annual Honour’s List, lets hear our leaders quote our artists past and present, let’s see artists bringing imaginative thinking to our corporate and government boards. Let’s see all our leaders showing that art is not a duty but a spiritual replenishment – I want to see Alan Jones espousing the rock art at Laura in northern Queensland, Bill Shorten at the Australian Art Orchestra, Julie Bishop at Belvoir Street, George Pell at Sisters Grimm (I think he’d get a lot out of it) – Gina Rinehart cutting the ribbon of the new Western Australian Centre for Concrete Poetry, and George Brandis proudly announcing a new scheme that sees five Australian books sent to every ten year old in the nation and a new Playwright’s Prize, in honour of Dorothy Hewett, to help keep alive not just the name of a pioneer, but to show Australians that as a nation we have an archive of national treasures and national treasure.

What is the artist’s role? To stand apart from authority, to be sceptical of power, to engage with human struggles and articulate them for others, to be free of cant, to embrace mystery, to be self-revelatory as a means of articulating the human experience and the determination to say what needs to be said.

Because if the artist does not do this – the ones who dare to imagine, who are liberated from punching the clock, who have no employer to answer to – if the artist does not fill this role of questioner, doubter, dreamer, warrior, iconoclast – then who will? And what sort of life would we have if those in power in any of our worlds: church, state, family, education, employment – what sort of life would we have if the law-makers in our lives never face judgement or analysis or criticism?

Isn’t the best society the one in which the powerful must persuade the people rather than dictate to them, must cogently defend their judgements, must convince us that their intentions are good intentions?

The act of provocation or scepticism to authority is not an act of terrorism or insurrection. The conventional wisdom that artists are all knee-jerk radicals intent on saboutaging conservatives, traditionalists and governments is a self-serving myth, which allows governments to denigrate artists, whose freedom they fear.

True artists are not unthinking radicals, although they can (and should) be radical. True artists do not promoting politics above creative expression. We are or should be fundamental independents, hostile to polemic, personal fiefdoms and political grandstanding, wherever we find them, in whatever corner of the Left or Right. Our independence is our heartbeat.

My oldest friends often remind me that when they came home from school with me, my Mother (who had spent all day teaching) would be lying on the living room couch listening to The Marriage of Figaro at full blast. My friend, Fiona, still has the handwritten reading lists my mother composed for her of absolute essentials: George Eliot, Thomas Mann, Jane Austen, Christina Stead, P.G. Wodehouse, Trollope… I never gave my mother my first drafts to read, although she asked for them, for fear that her opinion would suffocate my own and I would never know the writer I was distinct from the writer she wanted me to be.

But perhaps I should have had more faith. Mostly, her love for writing, for music, for art, and for the stories of everyone she met from taxi drivers to nurses to Nobel Prize winners was a love of life. I think she knew that the artist’s very existence is a declaration of love for the world around him or her. She knew that and it was wondrous to her and she infected others with that wonder, like some joyful contagion.

When artists stand up to be counted, we do so not from negativity or dogmatism, but from a profound engagement with our world and how it works, a connection to justice, and an unshakeable interest in humanity. Art reflects the world we live in, it explores our allegiances, it examines our suffering, it makes sense of our contradictions, it exposes our hypocrisy, it reveals our will to love and connect, it helps us face our failures. And all of this is driven by an often unrequited love for our audiences, for our society, for the wider world. This volatile engagement is the moral force of art.

The great late African-American writer, James Baldwin, wrote: “societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real.”

From Crikey’s The Rundown Daily Review here

Joanna Murray-Smith