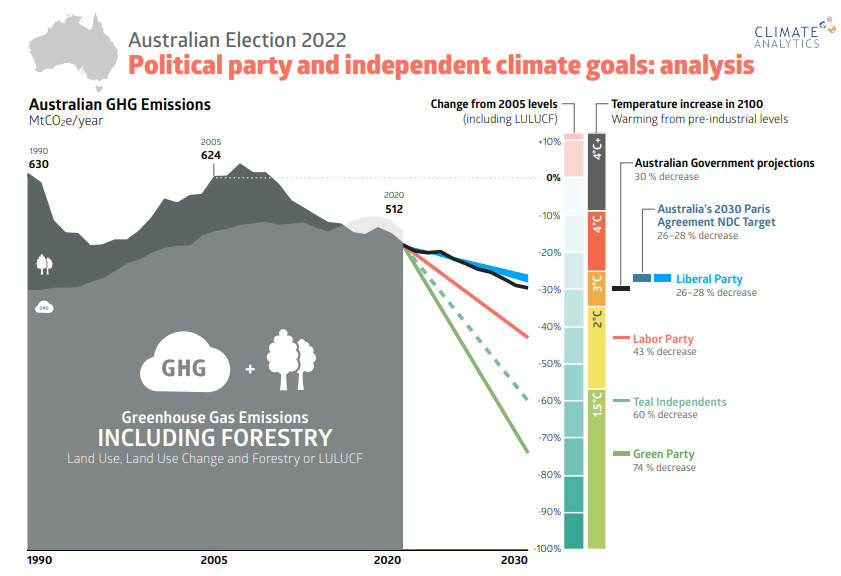

Report – Climate Analytics, 6 May 2022

Global warming rating of Australian political party commitments

One of the critical issues in the 2022 federal election is what position the major parties are taking on the top-level emission commitments for Australia. 2030 emission reduction commitments are a critical part of the Paris Agreement, and the UNFCCC had requested governments to update these for the Glasgow COP26 conference in 2021.

However at Glasgow Australia did not improve its 2030 commitment of a 26-28% emissions reduction, first made in 2015. In 2021 it resubmitted the same target to the UN as it had in 2015.

Under the Glasgow Climate Pact (2021), governments were requested to revisit and strengthen their 2030 NDCs this year, 2022, to align with the 1.5°C goal. There is a strong expectation on Australia to bring forward a more ambitious 2030 1.5°C aligned target by November at the UN climate Conference – COP27 – in Egypt.

Emission reductions for 2030 are very important if the world is to have a reasonable chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C, the long-term temperature goal of the Paris agreement.

At the global level total government commitments fall far short of the reductions needed in 2030 to be on a Paris Agreement compatible pathway. Countries such as Australia need to play their role in meeting the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal.

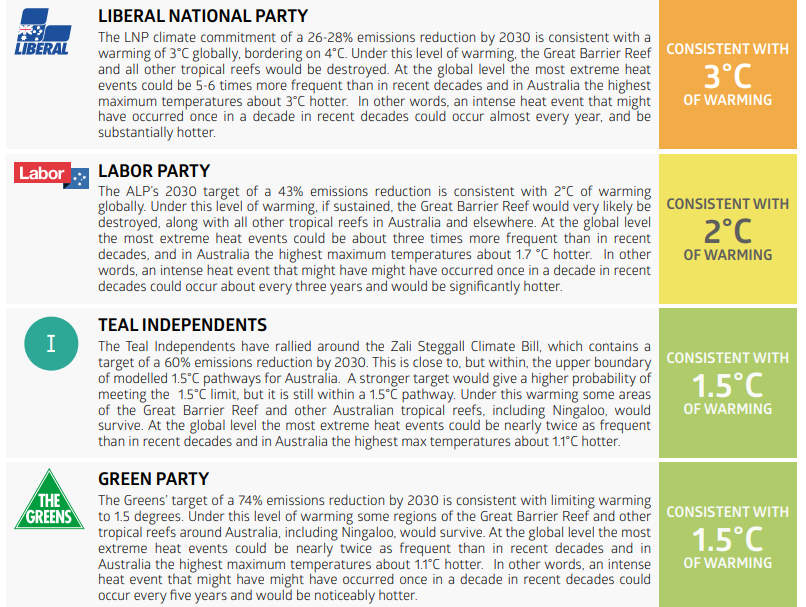

Australia has a direct and vital national interest in the world getting onto a 1.5° compatible pathway in order to protect its own natural ecosystems such as the Great Barrier Reef, agriculture, economy and health.

While the world has warmed about 1°C since around 1900 Australia has experienced an increase in average temperature of 1.4°C, with nine out of the 10 warmest years on record occurring since 2005. There is a clear scientific attribution of this warming to human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.

A decline in Australian crop yields is projected due to hotter and drier conditions, with heat and drought likely interacting to lead to greater losses. By the time the world warms over 2°C wheat yields are projected to decline, with a median loss of 30% in south-western Australia and up to 15% in South Australia by 2050.

The Great Barrier Reef has been seriously damaged by coral reef bleaching to date. Australia has experienced extreme, unprecedented wildfires, decreasing winter rainfall, and extreme, unprecedented rainfall events leading to catastrophic flooding. All of these climate risks are projected to accelerate rapidly with every increment of global mean warming.

It is possible to work out what individual countries need to do in terms of their domestic emission reductions to be on a pathway consistent with different levels of warming. Here we have used standard methods deployed by the Climate Action Tracker to provide a range of domestic emissions consistent with different levels of warming between the present time and 2030.

These emission pathways are drawn from complex energy system models that produced scenarios consistent with the 1.5°C limit in the Paris agreement and that have been assessed in the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C (IPCC SR1.5) and, more recently, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6).

There is no single pathway that is 1.5˚C compatible, so -consistent with their methodologies deployed elsewhere by the Climate Action Tracker – we take the range of pathways in the literature filtered with the sustainability constraints identified in the IPCC SR1.5. For the upper bound on each range of pathways for each temperature level we used the median of the set of scenarios consistent with each warming level. Emission ranges for each group are determined by those pathways that have a 66% or greater chance of holding warming below 2˚C, 3˚C, and 4°C. Paris Agreement compatible pathways are defined as a those that limit warming to below 1.5°C with a 50% probability and no or limited overshoot (<0.1°C).

It is important to emphasise that domestic emission reductions are only part of a government’s fair share contribution for the Paris Agreement, as that also requires wealthier countries to contribute climate finance to assist developing countries to reduce their own emissions. That means that even if a country’s domestic emissions are close to a 1.5˚C compatible zone, that country would also need to put forward sufficient climate finance, or further compensating domestic emission reductions, to achieve a similar fair share rating for its entire contribution to the Paris Agreement.

Here, we locate 2030 climate targets within bands of domestic emission reductions consistent with the different levels of warming globally if all other countries were to follow similar levels of action.

Emission reduction commitments in Australia have been expressed in terms of GHG emissions including land-use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF), and hence the top-level findings of this piece of work will be presented along those lines.

Nevertheless it should be noted that in Australia, LULUCF emissions and removals are highly volatile, and the amount assumed in 2030 has an impact on the level of emission reductions needed from greenhouse gas emissions excluding the land sector.

In Australia, action on greenhouse gases not including the land sector is fundamental to getting onto a 1.5° compatible pathway. We therefore show emission reductions both including and excluding LULUCF.

Read the full report here: Ausralian Election 2022 – Party Climate Goals (climateanalytics.org).